Camp3 Recce

Sarah Greenlees reports from the recce trip for an Arkitrek Camp

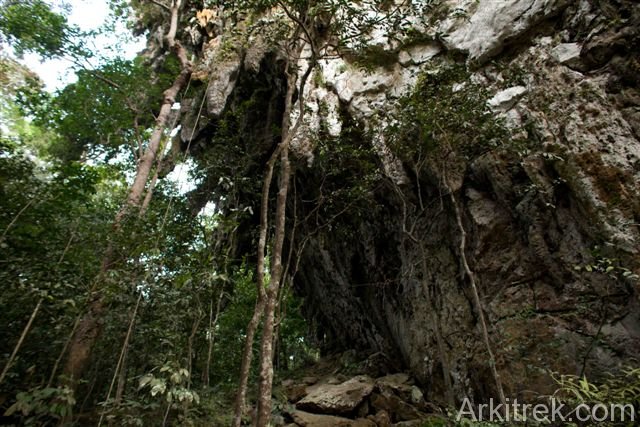

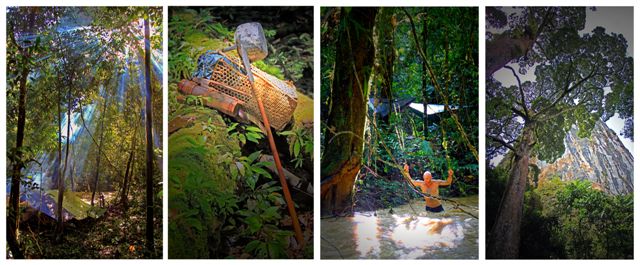

Last week I went on the recee for an Arkitrek Camp, which will take place deep in the Sarawak rainforest. I was expecting an exciting trip and within 24 hours we had trekked through spectacular primary rainforest; taken low canoes down forest lined rivers; scrambled up hills; slid down hills and stumbled across streams; we had eaten a variety of meats from eel to barking-deer and civet cat ; we had met villagers and learnt to use blowpipes; been fishing and hunting; explored limestone caves and climbed lianas to get views of forest covered hills and towering limestone pinnacles. This was far more of an adventure than I had ever imagined and that is all thanks to our gregarious and generous guides and hosts- the Penan of Long Ageng.

The Penan are the last nomadic tribe in Borneo and to describe them as resourceful would be an understatement. While we trekked in with packs heavy with hammocks, extra clothing and first aid kits, the Penan had divided a couple of key items between them- 2 cooking pots and a kettle, a couple of tarpaulins, 2 blankets and a fishing net. Within minutes of reaching our camping site they had built a comfortable shelter and had laid on a great spread for lunch. While we got eaten by mosquitoes and fought infected cuts and blisters, the Penan were untouched. While we stumbled and fell through streams, sliding off rocks and becoming unbalanced by the currents, the two young guys we were following jumped from rock to rock barefoot, catching frogs and throwing nets for eels to get breakfast for the next morning.

When, after caving, our hands were too dirty to eat with, the headman Jawa cut spoons from the trunk of a sapling and stitched leaves together to make bowls for us. When we got caught in a thunder storm he stitched large leaves together to make umbrellas. When we lost the propeller on our boat the next morning, a nail was pulled from the floor of the boat and used to affix a new propeller. The Penan seemed to carry nothing into the forest, but always had exactly everything that they need.

And so from this ease that they have with their environment I was able to begin to envision how the Arkitrek Camp might work. It will be tough and it will be a steep learning curve for the participants. There will be discomfort and tears I’m sure, and thanks to the ravenous, albeit tiny leeches there will certainly be blood, but I am also confidant that with the quiet and poised assistance of Jawa and his friends this discomfort will pass very quickly and everyone will settle into some sort of system with the forest. Learning from the way the Penan live in the forest I was also able to refine a kit list, sort out safety procedures and protocols, and work out the logistics of getting materials into such a cut-off place.

Returning from the forest, tired and somewhat beaten, we spent 2 nights in the luxury of the village. In the course of the final meeting to sort out logistics with the community, it struck me that the village was very egalitarian. On our trek, everything had been shared, be it pans or food or blankets. In other communities you might expect the headman to receive some sort of special treatment. However, Jawa had worked harder than everyone else to make the shelter and provide food and clean water. He was never without a pack and usually was carrying the kettle and a pan. We asked how the headman was picked and were told that people voted for the person that they felt worked the hardest for the rest of the community, the person that was the least selfish.

We had visited Jawa’s house. Instead of living in one of the longhouse lots with a big kitchen and sleeping rooms, he lived in a small 4m2 pondok (hut) on the edge of his tapioca farm. He shared this with his wife and son. The village leader lived in the most humble hut. When trips were made to live in the forest for months on end the women and children go as well. There seem to be little divisions. In our meeting with the community this seemed to be apparent as well. The women were having as much of an input as the men were. They were coming up with just as many ideas and questions. Their input was respected and valued. Throughout the meeting the Jawa held one of the village children as he fell asleep.

Of course, 4 days is not enough time to form an authority on a community, but it seemed to me that through all of the experiments of alternative living from communes to co-ops, what people were really trying to attain was what the Penan already had.

Before coming to Borneo I had never heard of the Penan. Deforestation was only an environmental issue. I didn’t realise it was also such a deeply social issue. As we left the village behind on the river and trekked back to the logging road that, that the threats to their way of life were so close and so out of their control. We learnt that they felt they could not keep up with modern developments and could not survive without the forest as a lifeline, and yet were prevented from even being able to do a simple thing like registering a vote. The politics are complex and the threats to their lives seem insurmountable. The list of endangered communities in Borneo exceeds just orang utans and sun bears, it also includes indigenous people.

And so the Arkitrek Camp is nearly on us. It will be tough, it will be sweaty and it will be a challenge of endurance; but it will also be a privilege to work alongside and learn from this incredible community. There will be a warm welcome and a family that will always welcome you back to their little bit of forest. And they will probably welcome you with civet cat!

Photos courtesy of Jesse Kip and Charlie Ryan

Hi Sarah

Impressive explorations! We’d like to link to your Arkitrek blog from the schools site if you would allow it. A brief intro blurb from yourself saying how you got involved and a piccie of you would allow us to make up a news item.

Best regards and take care out there.

Richy