Conservation or Animal Welfare?

In Sabah I am working on the design of a Sun Bear Conservation Centre, but is it really a conservation centre? In the course of my research for this project, a prominent conservationist suggested to me that its function was likely to focus on animal welfare.

This got me wondering. Where is the boundary between wildlife conservation and animal welfare?

As man continues to encroach on natural habitats, more endangered species end up in our care.

The dilemma we face is the balance between providing a good home for displaced wildlife and avoiding displacement in the first place through effective conservation.

It is important to distinguish between conservation and welfare because this will help assess the value of a project. If we see a lot of animal welfare projects this suggests that resources should be targeted at in-situ conservation projects to redress the balance.

Next door to the site of the proposed Sun Bear Conservation Centre is the well known Sepilok Orang-utan Rehabilitation Centre (SORC). The stated goal of SORC is to rehabilitate orphaned orang-utans. We presume that this means returning them to the wild with the skills necessary to survive.

In practice most orang-utans which arrive at SORC never leave the 5500ha Sepilok Forest Reserve. Here they live in isolation from other wild orang-utan populations at higher densities than might naturally be expected. Anecdotes suggest that the rehabilitation programme has released as few as 5 individuals into the Tabin Wildlife Reserve.

Dr Reza Azmi of Wild Asia has lamented to me that in some cases, particularly in Kalimantan, these sanctuaries are “the end of the line for orang-utans”. As deforestation continues there remain fewer and fewer viable natural areas to release future ‘orphan’ animals.

“The scariest thing is that these sanctuaries are becoming more common” says Reza and not just for Orang-utans but for other charismatic mammals such as Tarsiers and Sun Bears.

The Sepilok Orang-utan Appeal argues emotively that we have a moral obligation to try to care for these environmental refugees. This is true, but are we helping to conserve the species by doing so?

Supporters of the ‘sanctuary’ or ‘conservation centre’ argue that they fulfill a vital environmental education role which will filter down to public pressure for conservation.

“That is the Zoo philosophy” says Dr. Glyn Davies, WWF Director of Programmes and former Director of Conservation for the Zoological Society of London.

Environmental education is important but it needs to be carefully balanced with conservation work. Conservation means stopping and/or reversing habitat loss, preventing extinction and conserving populations of wild animals.

“As soon as you anthropomorphise an animal, you are no longer involved in conservation, but animal welfare” summarised Glyn. By this he means to give the animal human characteristics – like a name.

Glyn was commenting to me on a comparison between the Borneo Sun Bear Conservation Centre and the Borneo Rhinoceros Conservation Centre. I was having difficulty to understand why he thought that the Rhinoceros Centre was a bona fide conservation project and the Sun Bear Centre was not.

He explained that the Rhino project was trying to save a critically endangered animal from imminent extinction through a captive breeding programme (see my earlier post). This process relies on minimum human/animal contact and certainly no tourists who might upset these shy animals.

Conversely, Sun Bears are curious and adaptable animals and once accustomed to humans there is always potential for human/animal conflict if they are released back into the wild.

It seems that in Sun Bears vs Rhinos the difference between conservation and welfare comes down to their temperaments.

This doesn’t sound fair but the implication is that if we cannot re-establish wild animals from a captive breeding population then we are not directly helping to conserve them.

What we can do is provide better welfare for those captive animals and this in itself is a worthy objective. Animal Welfare means avoiding unnecessary suffering in animals in our care and can be neatly encapsulated by the so called five freedoms: Freedom from hunger/thirst, discomfort, pain/injury/disease, to behave normally and freedom from fear/distress.

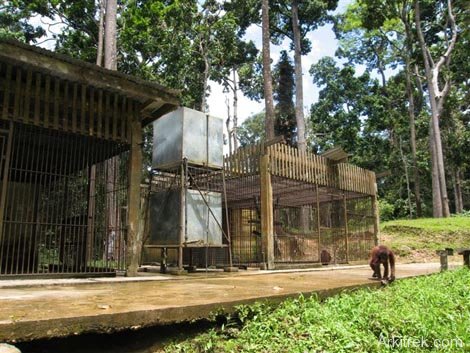

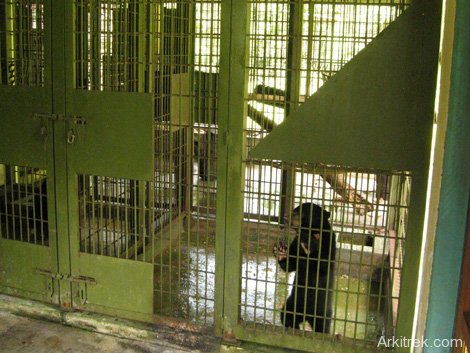

The Sun Bears at Sepilok are kept in small cages with no access to the outside. Almost all of them exhibit signs of distress such as excessive pacing and toe sucking. If there were no prospect of improving their living conditions the only humane alternative would be euthanasia.

The case for the Sun Bear Centre is further justified by the environmental education argument. For a large furry mammal, there is a surprising lack of awareness of this species in Borneo.

Compare them to orang-utans which are instantly recognisable to most people. In my opinion it would be difficult to justify more orang-utan sanctuaries or education centres on conservation grounds. For that species (and possibly primates in general) our energy is now better deployed on in-situ conservation.

A good example is the Hutan Kinabatangan Orang-utan Conservation Project (Hutan) started by French NGO HUTAN. This tackles the human/animal relationship by training the local community as field workers and developing community based eco-tourism dependent on wild orang-utans.

Unfortunately this kind of project cannot reverse the habitat fragmentation due to expansion of palm oil plantations. One way to do this is to leverage the public awareness campaigns of zoos and sanctuaries to raise money to outbid the plantations.

This approach has seen recent success with a campaign by World Land Trust and LEAP to buy up land in the Kinabatangan to be designated for conservation in perpetuity.

The future survival of Sun Bears depends on similar coordinated conservation strategies. Once the pressing need for animal welfare is met, there is exciting potential for the Borneo Sun Bear Conservation Centre to expand its influence to reverse habitat loss and conserve wild populations.

Related Posts

This is a very well reasoned discussion. It is also a serious dilmemma — what to do with all the captive orang utans. I have suggested in the past that European and American zoos should stop trying to breed orang utans (often claiming they do it for conservation as well) and provide homes for some of the orangs that are not suitable for release. I believe that a similar programme occurs in Belize with Jaguars that have been captured because of their depredations on domestic stock.

The problem is that there is a huge, unsustainable population of captive orangs, which despite the claims of some of the rescue organisations, have virtually no prospect of ever going back into the ild. In fact, because of theu=ir close contact with humans and human disease, in many cases it is undesirable they go back into the wild. In order for the ornags to survive in the wild, habitat protection has to be the number one priority. The problem is that land prices have escalated, and buying land is very expensive. However, it is still a cheap option compared with maintaining captive populations. But until the rich philanthropists of the world recognise that $1 million spent on habitats saves thousands of species — and until the majority of the wealthy of the world realise that the wild heritage of the world should be worth more than the billions spent of art and other artifc=cts of man, that can be reproduced, there is little hope for wildlife — even large charismatic species such as orang utans, let alone bats and frogs.

John Burton, CEO

World Land Trust