Indicators of Social Impact in Architectural Practice

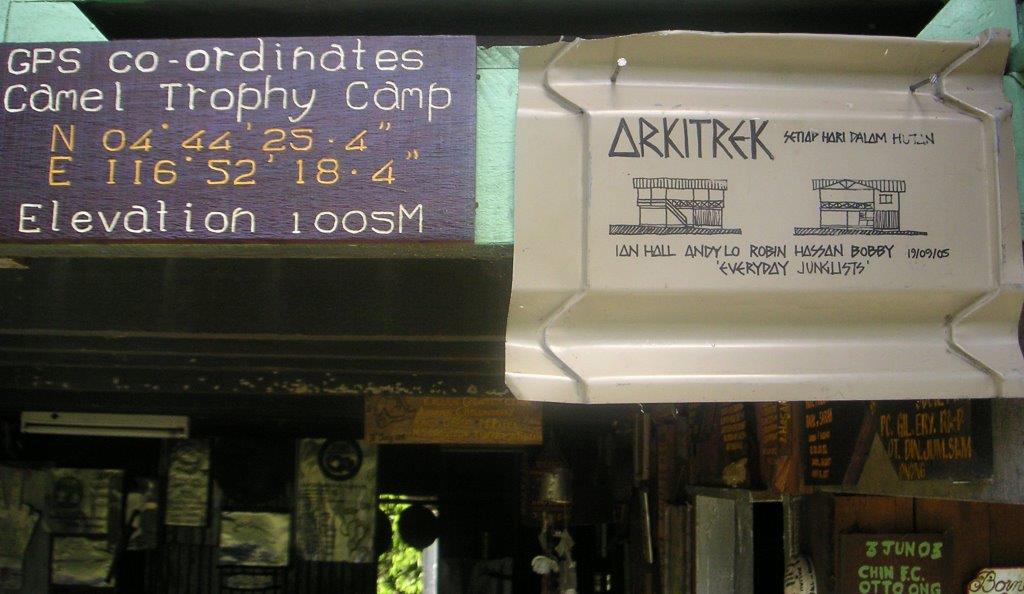

If you are an organisation with a stated social objective, then it’s reasonable to be asked to report how effective you are at meeting your objective. In a previous article we looked at some indicators that Arkitrek uses to report social impacts in architectural design. This article looks at the social impacts of how we do business, considering who we work for / who we do not work for, our staff welfare and our business philosophy.

Arkitrek has always only worked with clients who match our own social objective. This means that our design can amplify the impacts that our clients are making, which is significant because often our clients have potential to make a much bigger impact than us. Take for example, Borneo Rainforest Lodge (BRL). The income generated by BRL is a powerful argument for conservation of lowland tropical rainforest. BRL will be successful, not only because they have a location of extraordinary eco-tourism value, but also through the comfort and experience that architecture can provide for their guests.

Borneo Rainforest Lodge, Bornean Sun Bear Conservation Centre and SAFE project are all directly impacting nature conservation through tourism, wildlife conservation and ecological research, respectively.

Nanga Sumpa Lodge and Tinangol Community Centre are both good example of environmental and social impacts created through community based tourism.

Key clients of Arkitrek have always been rural communities, particularly those with potential for responsible stewardship of their bio-cultural heritage for example: sustainable management of fish and timber stock and using agricultural practices that conserve soil where it is useful, on the ground, rather than letting it pollute rivers.

BRL makes a good case study, but what is much more instructive is looking at clients that we have broken it off with. Choosing a client is like choosing a new romantic partner: they can often start off very rosy but end with dissatisfaction on both sides. Arkitrek has been around for long enough to have gone through a few break-ups. The following examples are all real, but they have been given a code name.

‘Mango Tree’ was a resort project proposed for a small inhabited island. The client’s view was that the inhabitants were not compatible with tourism development and she told them that they had to move, justifying her action with compensation payments. This is not to say that communities should never be moved to make way for tourism, but if they are to be asked to move then they should be allowed to give their free, prior and informed consent (FPIC). FPIC is an international protocol and was not followed in this case, making the project a non-starter for Arkitrek.

‘Alocasia’ was a project for a wildlife sanctuary, which on first impression seemed a good match for our philosophy. On closer inspection it had some problems: The first was that the client had a big budget for buying land for conservation. Apparently, their land acquisition strategy had the effect of pushing up land prices, which restricted the total amount of land that they, or other NGO’s, could buy for conservation. Secondly, they did not consult local communities on their plans, which resulted in conflict. We did not take this job because it was limiting the potential for nature conservation.

Fido was a boutique homestay project. The client came to me with a compelling and beautifully articulated social mission linked to the revenue generating homestay. She wanted the buildings to be a showcase for eco-design and sustainable living, so she said. Unfortunately after a year-long relationship she finally admitted “I want to be green, Ian, but not that green”

Moto was an easy project to turn down. The client wanted to over-develop his beach land in a way that would have completely ruined the natural beauty of the site, which was his unique selling point.

Finally the Me, Me, Me! Or MeMeme. We’ve had a few of these clients and they are often from our own impact sector. These clients believe that their own impacts or mission is so important that everyone else should work for them for free. Working for free is rarely going to help your social enterprise to survive and create sustainable impacts. What’s more, by working for free you may be depriving someone else of work, creating a negative social impact. More about this in The Arkitrek Guide to Working for Free

Arkitrek founder, Ian Hall, found business inspiration in Yvon Choinard’s book, ‘let my people go surfing’. Here, Choinard questions the concept of ‘sustainable economic growth’, blaming the degradation of natural systems that sustain life on earth solely on our drive for endless growth.

If Arkitrek designs buildings to conserve nature; then the way that we want to do business is to displace the need for endless growth that destroys nature. Social entrepreneurship may help to do this, by balancing the imperative to return money to private shareholders with the imperative to create opportunities for a wider community. In this way creating social gains rather than private gains.

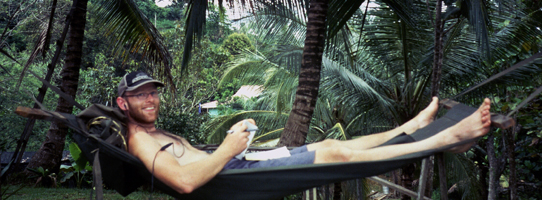

Choinard’s philosophy of ‘let my people go surfing’ is indicative of a social impact culture within the company itself. Staff training and welfare are at the heart of a Social Enterprise. Above, the Arkitrek team is being trained in ‘stick twirling’ by our intern and sensei, Chris. The synergy here is attracting and retaining the staff who have most to offer, supporting their personal development and giving meaningful employment and a decent salary.

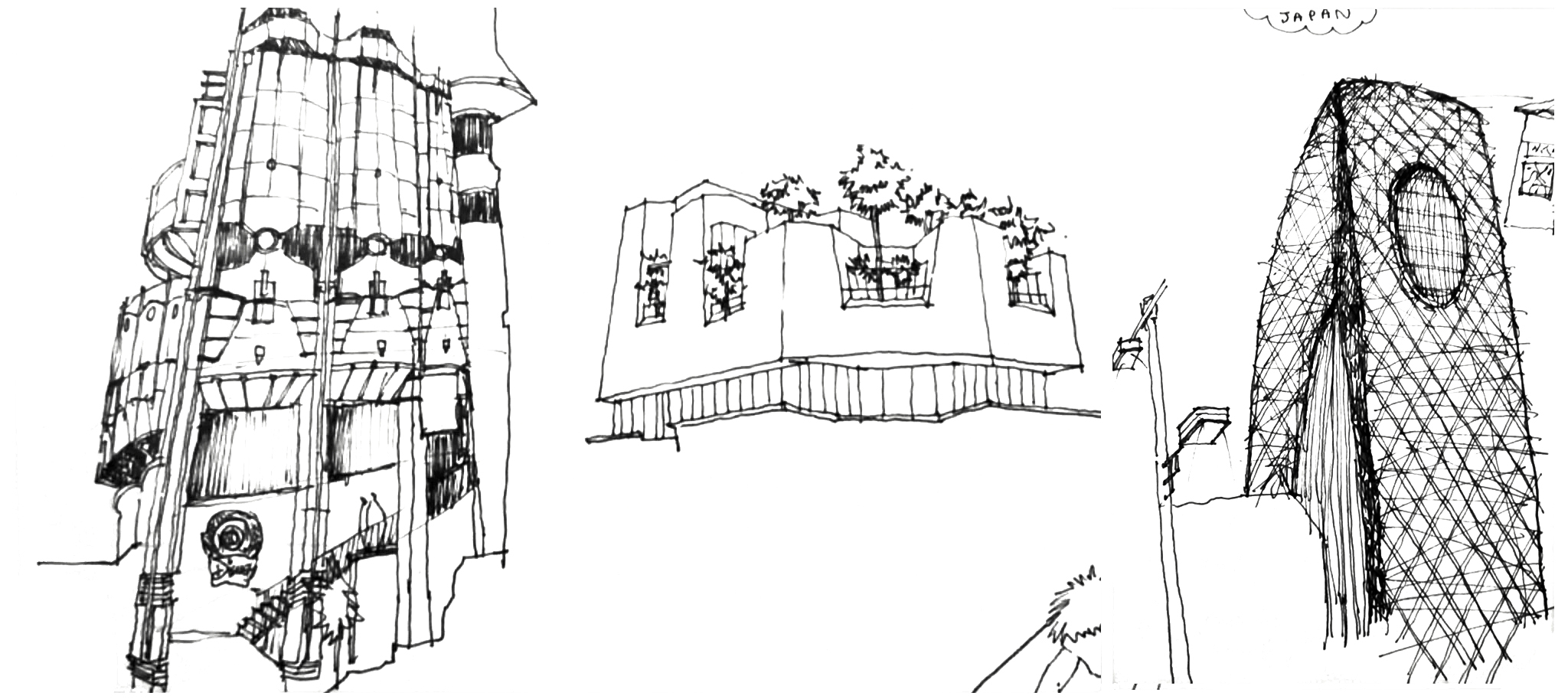

Whether freezing on the Greenland ice cap or sweating in the Bornean jungle, it’s easy to feel how small and fragile is our place in the world and what enormous social impact can be created by the changing of natural systems. We’re well enough informed to know some of the impacts of loosing either the rainforest or the ice cap and yet what difference can we possibly make? Rather than being intimidated, we can use the beauty of nature as inspiration, to remind us to keep asking difficult questions and looking for hidden connections, and remember that some things can only be valued in units of wonder.