Architecture learning from Responsible Tourism

“The Role of Architecture in Responsible Tourism” was first published in FuturArc Magazine, Issue No. 4Q 2012, p.86. The following text has had the first four paragraphs of the original edited down to two and the sidebar about Arkitrek removed. In all other respects the text is identical to the FuturArc article.

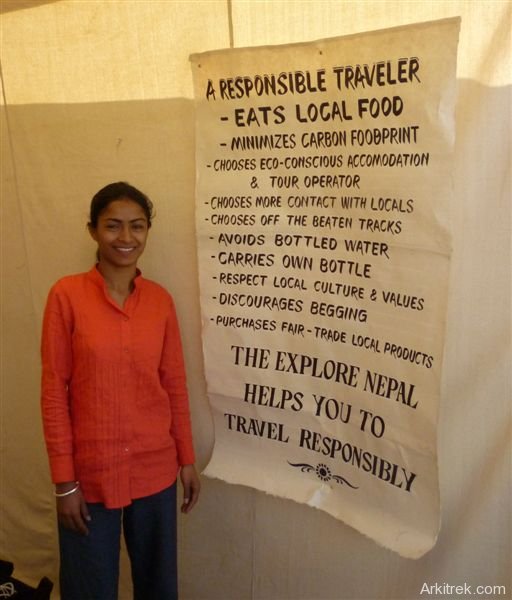

Exotic cultures and outstanding natural beauty are the social and natural capital of a large sector of the tourism industry. An emphasis on economics, society and environment is now enshrined in global responsible tourism standards . Green Building standards, focussed largely on technical issues, can learn a lot from the social gains derived from responsible tourism.

This article looks at architecture which develops infrastructure on the RT ethos of protecting natural resources and creating models for social return. This includes social infrastructure and returns to the local and wider community. Educating designers to work in such a mindset is imperative to the sustainability of the concept itself.

Extending social gains through design and education

Design-Build

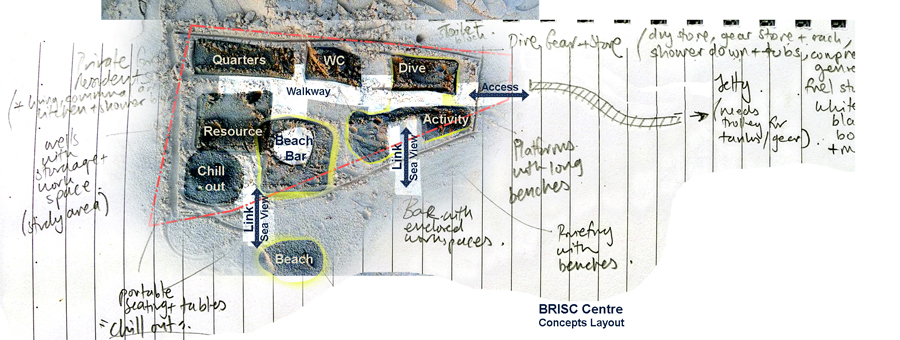

In May 2012 Arkitrek, a Malaysian design company, asked a team of students to build a bunkhouse on the island of Mantanani in Sabah. The students’ design brief came from Camp Mantanani, a community based tourism operation on the island. They were asked to respond to the environmental issue of groundwater contamination and over extraction. The team was facilitated on-site by David Arnott (28) a UK architect who had himself, participated in a similar programme the year before. The Mantanani Bunkhouse team rose to the challenge with quiet confidence and crafted a building of sophisticated details and inventive material specifications.

The participants learnt first and foremost about design and construction. Anna Nicholls (21) an architecture student from University of Sheffield, UK had a startling realisation:

“The project heightened my sense of special perception and awareness in comparison to just designing through drawings in an office or studio. I have realised that even small differences in dimensions can make a large difference to how it feels to inhabit a space”

Project workshops teased out a design for which there was no sole ownership. The team learnt collaborative design techniques that ensured that every team member made a valuable contribution. Another lesson came from the brief itself: how architecture can both raise the awareness of and provide a solution to an environmental issue. In this case it was through prototyping rainwater harvesting systems and running awareness workshops with the local community and school children.

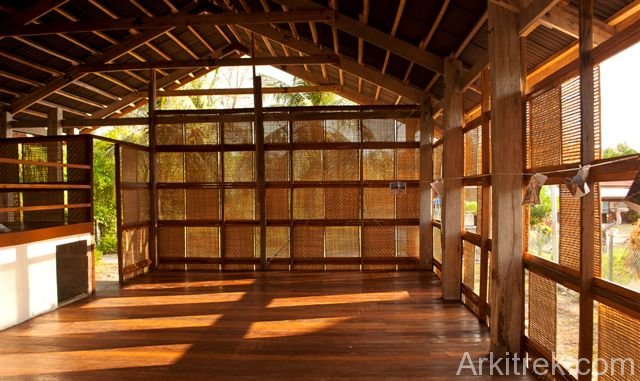

More subtle lessons were learnt as well; the island’s natural beauty inspired a desire to protect and make wise use of the islands natural resources. For example, participants were keen to use driftwood and employ local labour to machine it, rather than importing resources that would have no direct impact on the community. And, when looking for a façade material, the labour intensive process of weaving palm leaves was chosen. Not only is it a readily available resource, it also provides opportunities of enterprise amongst the community. The fact that these materials have a quicker delivery time, no transportation cost and support the local community made it an easy decision and fostered the principle of searching the locality, be it rural or urban, for materials and skills that could be adapted or reinvented.

The result was a sophisticated design-build- an exploration of rational design with natural, unrefined materials that integrate environmental conservation methods with social returns which provides a precedent for further development.

“This truly has changed my perception of architecture. I didn’t think it would, and I’m not one for radical shifts in my thinking. However, being back with people that are so passionate about design is infectious. The greatest thing about the camp is that I have rediscovered my love for architecture and I am going to work very hard to let this inform all my work back in Scotland.”

David Arnott, Arkitrek Camp Participant May 2011

The Mantanani community is isolated from the rest of Sabah with little education or awareness of pressing environmental issues. However, from working alongside the students, the Mantanani islanders have come to acknowledge that foreigners value things that they do not. For example, that driftwood can be beautiful in its natural state and that handcrafted materials, such as bamboo or palm weave, can make a respectable building facade. They also learnt that tourists use a lot of water and therefore have grudgingly accepted bizarre practices such as collecting rainwater and recycling waste water.

The fact that this design-build programme operates within a responsible tourism operation is no accident. Tourism provides the financial returns that make investment in people and buildings possible. The approach taken by these students to adapt local skills and materials is not always easy, there are cultural hurdles to overcome and in isolated and conservative communities these can be significant.

Tourism also provides a long-term relationship with the community and the commitment to establish sustainable operations. Camp Mantanani is one of three tourism operations set up by UK based Camps International to develop tourism infrastructure within rural, under-developed communities. On land rented from community, with a staff almost entirely from the same community, they cater mostly to school groups and gap year volunteers. The volunteers get an authentic, off-the-beaten-track experience of rural Borneo and in return the communities get responsible tourism on their terms. Since Camps International started operations on Mantanani, the local staff have learnt English; become more informed about environmental issues and gained confidence in interacting with foreigners. They have on their own initiative reinvigorated traditional dance and handicrafts and received training to become dive-masters and managers.

Volunteer Tourism in Nature Conservation

In another example of hands-on tourism the Borneo Sun Bear Conservation Centre (BSBCC) engages volunteer tourists to assist in construction projects. BSBCC aims to enrich the welfare, rehabilitation, education and research concerning the Malayan Sun Bear, a totally protected species in Malaysia. Although the BSBCC buildings and major infrastructure are carried out by professional contractors, volunteer tourism has been used in the design and construction of peripheral infrastructure. The Bear Action Teams (BATS) programme engages groups of volunteers in small design and construction projects, that are supervised and facilitated by architectural students.

The programme has already built an entrance bridge and disabled access ramp, screening between public and private areas, forest enclosures and perimeter boardwalks. Currently the BATS programme is designing and constructing sun bear enrichment installations for the forest enclosures. All of these elements have been constructed from reclaimed hardwoods, rather than newly logged hardwoods.

To date, more than 33 groups of volunteers have participated in the programme, and over 700 individuals have directly contributed skills, time and resources to the bears. The advantage of this model is a higher social return of direct involvement of individuals in conservation, in the belief that this will make them stronger advocates for sustainable development. The model itself is instrumental in that it allows large number of people to get involved in environmental projects.

Development of locally produced natural materials

Both of these tourism models are based on low environmental impact while creating opportunities for high social impact. Can this model can be applied to the specification of material, an intrinsic element of sustainable design?

Lime:natural fibre composite concrete, or bio-crete, is a concrete-like material with a low carbon footprint and efficient insulating and hygroscopic properties. ‘Hempcrete’, a proprietary biocrete product is now enjoying widespread use in Europe. Biocrete has the potential to create social gains by adapting the material to use locally available natural fibres and open-sourcing the mix and methodology. By developing the material with local natural fibres it not only reduces embodied energy of transportation, but it also has the great potential of providing an opportunity for enterprise in remote communities; ranging from fibre collection and preparation to dry mix production and marketing. Open-sourcing the research extends these opportunities to more people and more villages. Locally sourced natural fibres such as rice-husk, coconut coir and palm plantation waste fibre are being integrated in concrete mixes with great success.

In another direction, Sabah has a tradition of high quality bamboo and rattan weaving for handicrafts. However, the transition of this traditional skill into construction is rarely seen. In a design that came from an architecture student watching village ladies sifting rice in the traditional bamboo weave winnowing trays, thin strips of bamboo are woven into panels and bound in a frame. The panels have been developed as a facade system for a community learning centre on Mantanani Island and have further application for fencing and screening. The design is a collaboration between a village in the north of Sabah and architectural students. Through reinventing traditional weaving skills for the construction industry the opportunities for enterprise within the village have been broadened.

The weave of the panels are designed in response to the requirements of privacy, light, ventilation and aesthetics. In the learning centre the panels create a collage of weave patterns that become more open towards the top of the elevations. This provides privacy at low level, where the sun is also the harshest, and allows cool breeze to filter through under the shade of the roof overhangs. The bamboo programme is now being extended to other villages around Sabah, extending the opportunities for enterprise to other villages while also extending the breadth of expertise involved in the development process.

In the same manner that responsible tourism seeks to protect the intrinsic value of an unspoilt natural environment, these materials should protect the source of the natural material by its very demand for it. As responsible tourism should not harm societies, but provide support for existing cultures, these materials provide new markets for traditional skills and pride in the people who produce them. The programme has so far involved architecture students, engineering students as well as volunteer tourists and communities. The social returns are immediately apparent in the same manner as they are at BSBCC; through the large numbers of people directly learning and benefiting from the project.

In the future, sustainable design and green buildings, be it rural or urban, will come to mean much more than a technical fix. The architecture of sustainable design will be about building a social infrastructure of jobs, skills, culture and pride. It is about sharing the benefits of development with as many participating people as possible. In other words, it will be very similar to the principles already enshrined within the ethos of Responsible Tourism.