Mt Kinabalu Melangkap Route

‘There’s a new route from Kampung Melangkap’ said Jasirin my mountain guide friend.

My interest was piqued immediately

‘Have many people done it?’ I enquired

‘Yes lots’ he replied. I was deflated.

‘But only villagers’ he added. My imagination took off again and for some reason the word Melangkap got caught in the mesh of my sieve like brain.

About a month later I received a call out of the blue from Graeme Shepherd an old climbing friend of mine from Dundee whom I had not seen for six years. Graeme and I had met in my last months at Dundee University. That this was barely enough time to form a friendship did not deter Graeme from inviting himself to stay with me during my post university sabbatical in New Zealand. Together we enjoyed three weeks of travel and rock climbing in the North Island and our friendship was sealed. However, apart from sporadic email contact that was the last time I heard from him until now.

‘Are you still in Borneo?’ Graeme enquired tentatively by email. Based on past form I thought I could see where this was leading. A week later he had booked his flights and was coming to visit me. It transpired that he had just finished Medical School in Brisbane and wanted a three week blow out. His ambition was to see proboscis monkeys and orang utans and also to visit Mt Kinabalu. It was now down to me to juggle some time off and come up with an itinerary.

For the first week of his trip I had work commitments so I suggested that he take off to the Kinabatangan River to see some monkeys. In the second week I was sure that I could get us into the Danum Valley Field Centre. This just left the third week. I remembered Jasirin’s words; the route could be done in five days he had assured me. Would Graeme be up for it I wondered? More importantly would he be up to it? I had not seen the guy for six years; he could have become fat and sedentary during his time at medical school. Somehow I doubted this but even so I knew that the climb would be challenging and so I pointed Graeme at the trip report of my Mt Kinabalu Eastern Ridge Expedition to give him an idea of what to expect. I could see that he was apprehensive but I was confident that we could succeed.

On our second day into the expedition Graeme confided in me ‘you told me that it was going to be hard but I didn’t realise it was going to be this hard!’ We had been on the go since dawn and it was now nearly dark. The first part of the day had involved wading up a boulder strewn stream bed with occasional detours into the jungle to avoid deep pools and waterfalls. At mid morning we left the stream and abruptly started climbing. The ground was loose and I had to dig my fingers into the mud or grasp at wild ginger to avoid a slide back down into the gorge. I was glad of the studded soles of my fell running shoes. As we got higher the angle eased off and we could stand upright without using our hands.

Walking under the tree canopy dulls the sense of distance but heightens your awareness of the immediate proximity. This is just as well when the footing is not always stable, overhead branches wait to snag your rucksack and every potential handhold must be assessed for spines and structural integrity. With no views for orientation it is only the shape of the ground that gives a clue to progress. For a while I was aware that we were following a ridge line, at other times we were climbing a steep face. At one point we scrambled up a small watercourse and paused to refill our water bottles. Shortly after this the ground levelled out and we reached a camp site. Our itinerary did not allow for the luxury of a half day trek and so we pushed on, aware that the water we were carrying may have to last until the next day.

Our objective was the Penataran River. I had no idea what this meant other than Jasirin said that that this was where the next water supply and a camp site could be found. Later, on inspecting the map I found that this river drains the infamous Low’s Gully. We were to join it upstream of the confluence with Low’s. The trail traversed the hillside now and the mountain dropped into gloom to our right. Progress was slowed by barbed rattan which clawed at the skin and made an unpleasant tearing sound as it dragged across our rucksacks. The leeches which had been bugging us all day were now starting to get unbearable, my socks were soaked with gelatinous blood and the bites were starting to itch. It had not rained but my clothing was soaked and the sweat stung where it ran into scratched skin. It started to get dark and my fears of not reaching the campsite came sharply into focus. At this point we lost the path.

All day I had been surprised by the quality of the trail. Although steep and at times treacherous it was generally easy to follow and if in doubt regular blazes on trees confirmed its course. It was clearly well used by villagers, presumably as a hunting trail. At this point however a large fallen tree had obliterated all signs. While I checked out the hillside for flat areas that might fit our tent, Jasirin and our porter Girul circled the tree fall looking for the trail markers. Just as I had scraped out a bit of level ground Jasirin reported that he had found the trail. I was inclined to stay put until morning but Jasirin convinced us that we might still reach the Penataran before nightfall.

We started off again steeply downhill and soon we could indeed hear the roar of a river, but it was still far below. Jasirin ranged ahead, terrier like and we followed on as best we could. A steep off balance move over some rotten logs lead me through a band of small cliffs into a dry watercourse. I passed it without incident and remember hearing Graeme behind me mutter ‘this is dangerous’. Moments later I was aware of trauma and turned to see him embracing a 10 foot section of dead tree trunk that had come free of the hillside. For a time-stand-still moment they pirouetted together and eventually both managed to stay on their ledge. We were shaken but there was no time to gather our thoughts. We plunged on down skirting steep cliffs and pushing through thick vegetation. Meanwhile the gloom thickened.

‘Not enough time’ confessed Jasirin, but he had found a campsite. One side of the tent overhung the edge of the path while the opposite side was dug into the hillside. The tent door was propped up by a sharp boulder. Jasirin and Girul’s campsite was even smaller. Dinner was instant noodles, there being no inclination to attempt something more elaborate. As night fell the insects came out and I batted away a cloud of small biting flies while I attempted to tidy up our dinner utensils. With relief I finished my chores and bundled into the tent and zipped up the insect mesh. It was no use, the mesh was too large and the flies came through. We hung up a torch in the porch to keep them outside. There was no question of going straight to sleep, our feet and legs were a mess and needed attention.

‘Not enough time’ confessed Jasirin, but he had found a campsite. One side of the tent overhung the edge of the path while the opposite side was dug into the hillside. The tent door was propped up by a sharp boulder. Jasirin and Girul’s campsite was even smaller. Dinner was instant noodles, there being no inclination to attempt something more elaborate. As night fell the insects came out and I batted away a cloud of small biting flies while I attempted to tidy up our dinner utensils. With relief I finished my chores and bundled into the tent and zipped up the insect mesh. It was no use, the mesh was too large and the flies came through. We hung up a torch in the porch to keep them outside. There was no question of going straight to sleep, our feet and legs were a mess and needed attention.

Leeches first inject an anaesthetic so you don’t feel their bite, then they inject an anti coagulant. The blood keeps oozing often for hours after the leech has dropped off. To add to our discomfort there were rattan scratches, grazes from logs and rocks and now as the final straw the midge type insects were joining the feast. Stripped down to boxer shorts I dampened some wet wipes and vigorously rubbed down my legs. I then repeated the process using iodine soaked wet wipes. The final stage was to break open some anti-histamine capsules, mix the powder with a little water in our grubby hands and rub this onto our legs. My whole body seemed to itch and the sharp rock by the door precluded any comfortable sleeping position. In vain I told myself it was mind over matter.

‘I’m going to count to 100’ I announced.

I did not even make it to 5 before I was scratching furiously again. Relief was a long time coming.

In the morning it took us another half hour to reach the Penataran River. I exploded my kit gratefully on the moss covered boulders and washed out our pots and pans plus my foetid socks. Overhead a ribbon of blue sky matching the course of the river told us that it was a fine day. So far we had been lucky with the weather, although I did not mention this for fear of tempting fate.

‘So remind me again’ announced Graeme, ‘this is our point of no return right?’

Graeme had a flight to catch and this meant that we were compelled to do the route in five days. Now on our third day our commitment to completing the route would become binding. In reality the thought of retracing our steps had already become unthinkable.

Back in Kundasang before starting the expedition we had emphasised our five day deadline to Jasirin. With a flourish he had produced a brown school exercise book who’s only content was a centrefold spread featuring a long wavy line with shorter lines crossing on the perpendicular. I immediately recognised it as a map. This was a major advance for Jasirin and he started adding little triangles to indicate the campsites used by the previous expedition. On this ascent Jasirin himself had been guided by a local hunter and their group had comprised 10 Sabah Parks’ personnel. We counted up the nights which to our consternation came to 7. We started to object but Jasirin was ready for us with a new proposal; we would do the route in reverse!

This seemed to make sense to me because by starting up the tourist path would reduce the amount of ascent we would have to do and presumably also the duration. Jasirin started counting out his proposed camp sites on the map in reverse. They came to 6 but towards the end he hesitated and became confused.

‘We need a rope to cross this river’ he said

‘How deep’ I asked. He indicated chest level and went on to add ‘this other river we cross 14 times’

I caught onto what was worrying him. ‘What happens if it’s in flood?’ I asked.

His lack of an answer told me all I needed to know. We could get four days into the trip and then get stuck on the wrong side of a river. With Graeme’s deadline this was an unacceptable risk, especially as we were technically climbing in the rainy season.

Back to plan A. This way if the rivers were in flood we would encounter them in the first half of the climb and have time to retrace our steps. Jasirin started counting out the campsites again. This time they came to five, it looked like we had a deal.

‘So remind me again’ said Graeme, ‘the 10 guys from Sabah Parks did this route in 8 days and we’re trying to do it in 5?’

‘They were not strong’ explained Jasirin, ‘fat’ he added with pursed lips and an expansive hand gesture.

He got the ‘map’ out again and counted our campsites. This time they came to 4. We could be on our way down the day after tomorrow he suggested. I looked up into the trees. Although I could not see it my GPS told me that there was still 2500m of mountain above us. I trusted Jasirin to get us through but did I trust him enough to gamble on Graeme’s flight? Graeme had not climbed with Jasirin before so had little upon which to base his trust. It was a brave decision for him to continue but then as I have mentioned, to go back was already unthinkable.

The water level in the Penataran was low and we managed to keep our feet dry by boulder hopping. Once again we were carrying two days water and were trying to do two of the previous expedition’s days in one. After crossing the river we passed a comfortable campsite before launching into the climb. It wasn’t long before we reached our first ‘granny stopper’. This is an affectionate term for a short section of climbing on what is otherwise a walking trail. Our way was barred by an overhanging section of rock from which dangled some taunting tree roots. Jasirin was into these roots like a rat up a drainpipe and soon had a rope dangling from the top. Once he’d hauled my pack up I felt a little more confident. I found two good roots to hold onto and started working my feet up a greasy pole thoughtfully provided with parang notches by village hunters. Just as I was attempting to high step and rock over onto the flat of my hands, my right foot slipped and I was left dangling instead. I knew the move now though and stuck it on my second attempt.

The water level in the Penataran was low and we managed to keep our feet dry by boulder hopping. Once again we were carrying two days water and were trying to do two of the previous expedition’s days in one. After crossing the river we passed a comfortable campsite before launching into the climb. It wasn’t long before we reached our first ‘granny stopper’. This is an affectionate term for a short section of climbing on what is otherwise a walking trail. Our way was barred by an overhanging section of rock from which dangled some taunting tree roots. Jasirin was into these roots like a rat up a drainpipe and soon had a rope dangling from the top. Once he’d hauled my pack up I felt a little more confident. I found two good roots to hold onto and started working my feet up a greasy pole thoughtfully provided with parang notches by village hunters. Just as I was attempting to high step and rock over onto the flat of my hands, my right foot slipped and I was left dangling instead. I knew the move now though and stuck it on my second attempt.

With increasing height the trees started to thin out and the trail brightened up. This extra light brought with it more ground vegetation and we waded through waist deep rustling dipteris leaves and ducked under gnarled leptospermum branches. Large pitcher plants were abundant of the species Nepenthes Villosa and Edwardsiana and on the rim of one pitcher we found a tiny frog with a bright orange nose.

We climbed continuously all day with frequent steep root ladders to negotiate. By mid afternoon it started to rain gently and I could tell by my laboured breathing that we were close on 2500m altitude, the height at which I usually start to feel the onset of mountain sickness. I was stopping regularly for rest now and my throat was parched. Jasirin told us that we may not find water until the end of the next day so I could not risk drinking too much. I took some comfort in sucking refreshing droplets from the waxy leaves that I brushed past. We had passed a campsite at lunchtime and it was clear that we were not going to reach the next one before dark. Anxious not to repeat last night’s discomfort Graeme and I resolved to stop when we found some flat ground rather than carry on until nightfall. Fortunately we were now following a ridge that undulated gently and soon reached a broad flat area whose soft mossy ground had recently been dug over by wild pigs.

The next day I was looking forward to getting my head above the trees. Until now the only view of the mountain had been a glimpse from our enforced camp on day 2. Through the trees I had seen a near vertical ridge silhouetted sharply against the fading light. My imagination filled in the parts that I could not see and although it was across the valley the prow seemed to be hanging above us. So intimidating was the feeling that I hesitated to point it out to Graeme. From out of this foreboding came a tremble of excitement. As improbable as it felt, somewhere through the steepness and mist was a way up this mountain.

Now on our fourth day we did not have long to wait to get our first view. It came fleeting at first, framed by twisted branches and eagerly sought from tiptoes on boulder vantages. I forgot my breathlessness and climbed fast to break free from the grip of the forest. When at last I felt space all around me I found Low’s Gully at my feet. Across that improbable defile were ranged the cliffs and spires of the Western Plateau. It was a rock climbers’ paradise but mostly hideously inaccessible. At the base of clean granite walls a subtle shift in angle and elevation allowed vegetation to take hold. These inhospitable slabs disappeared out of sight into the roots of the mountain. Round to the North was the only marginally more amenable Penataran valley and beyond that we could see the cluster of houses at Kampung Melangkap Kapa where we had started our trek so far below.

‘Mr Bean, Mr Bean’ the Kg Melangkap school children had tuanted us earlier, at the start of our climb. I evilly hoped they were referring to Graeme.

‘Who is Mr Bean’ I challenged them.

‘He is!’ they chorused. I felt smug.

‘And you are Mr Bean too’ they added. Or was that ‘Mr Bean Two’?

‘Drink, drink!’ urged one of the cooking women, and for once it wasn’t rice wine. We were supping on hot sweet sago drink mixed with lentils and some other unidentified bits. I had caught some sun during the morning and the drink was refreshing. On the slog up to the village we had been passed by several men coasting down on their motor scooters. Across the panniers were draped what looked like dirty white door mats. A pungent smell confirmed their cargo. Natural rubber was fetching a good price these days, nudged up by the hike in crude oil prices.

Kampung Melangkap Kapa is at the end of the road, hidden in the lower folds of Mt Kinabalu. The village is perhaps best known as the base of rescue operations for the ill fated British Army Low’s Gully expedition. The gratitude of the soldiers is represented by a new village Resthouse. We could not help wondering that given the state of some of the children whether provision of ongoing basic healthcare could have been a more valuable contribution.

I have come to know many of the Dusun people who live around the Mountain and I’m lucky to count some of them as close friends. Jasirin and Girul are from the same stock. Life cannot be easy in some of these villages and yet they always manage to extend unconditional hospitality. After the sago drink we were served huge plates of rice with steamed jackfruit and small dried river fish. We ate to the accompaniment of the afternoon rain drumming on corrugated iron. On cue the rain stopped and we wended our way out of the village through crops of bananas and hill rice. Further out we passed small rubber and pineapple plantations before entering the rainforest.

I have come to know many of the Dusun people who live around the Mountain and I’m lucky to count some of them as close friends. Jasirin and Girul are from the same stock. Life cannot be easy in some of these villages and yet they always manage to extend unconditional hospitality. After the sago drink we were served huge plates of rice with steamed jackfruit and small dried river fish. We ate to the accompaniment of the afternoon rain drumming on corrugated iron. On cue the rain stopped and we wended our way out of the village through crops of bananas and hill rice. Further out we passed small rubber and pineapple plantations before entering the rainforest.

The forest has long been important to these villages; as a source of water, construction materials, meat, medicinal plants and much more. At Melangkap there is a blurred boundary between rotating cultivation, secondary scrub and primary forest which occurs at about 750m altitude. By contrast around to the south near Kundasang and Mesilau the transition is abrupt, in many places primary forest has been completely cleared up to 1500m altitude. The reason for this stark difference is attributable largely to agriculture. The inhabitants of Kg Melangkap practice subsistence agriculture with limited cash crops whereas Kundasang is renowned for market gardening; growing everything from cabbages to carnations, mushrooms and houseplants.

Another reason for the difference is accessibility. The main highway linking the East and West Coast of Sabah crosses the mountainous spine of the Crocker Range at Kundasang to the south of Mt Kinabalu. At this point the road reaches an altitude of over 1600m making exploitation of the cooler uplands much more feasible. At Melangkap a downed bridge on the dirt road meant that we started walking at 250m above sea level. It was no wonder that later on as we looked back, our starting point appeared so hazy as to be disconnected from our reality of bare granite and clear mountain air.

For a while Low’s Gully was hidden from view, concealed behind the North Peak. As we passed I fantasised about new routes on a pyramid of impeccable granite. My reverie was interrupted by a trickle of water held in a mossy depression. Thirstily I gulped the last of yesterday’s water and refilled. Carrying the extra four kilos seemed to be immediately compensated by being hydrated again. We skirted the summit of North Peak and descended to a gap in the ridge. I could now orient myself from my previous expedition. Down to our left was the gentle sweep of slabs leading into the Mekado Valley, site of our penultimate camp when I climbed Kotal’s Route in 2004. To our right Low’s Gully was back with a vengeance.

The last hour of our climb to King George Peak followed the North Ridge, by now an easy angled incline but with the ever present void nipping at our heels. Out of the Gully rose towers of blinding white cloud. The contrast was intense and the cloud was always shifting so sometimes we could catch glimpses of airy ledges perched over nothing and at other times the peaks of the Western Plateau just floated detached from the earth. With the binoculars we searched down past those ledges trying to measure the depth of the Gully. It was an impossible task, the bottom of that gully might as well be on another planet and I hold a mixture of envy and disbelief for those who have ventured into that world.

Up on the North Ridge the silence is deafening. There is no where else that you can experience this sound, except on a mountain top. It is as oppressive as it is enlightening, both humbling and uplifting. Listen too hard and you’ll get vertigo, it’s best to keep moving. The altitude drags at my feet but my lungs have its measure. I arrive for the second time in my life at King George Peak. There is no point drawing comparisons, this is now and we have a night in the open to look forward to.

‘Red Rocks’ Says Girul, ‘there is a sheltered campsite there’.

Graeme and I agree that even though our tent would not withstand a storm up here, it is more appealing to risk this than descend to the squalid hut at Laban Rata.

Red Rocks does exactly what it says on the tin and we pitched tent beside a house sized boulder. No sooner had we finished when Jasirin pointed out that if it rained our campsite would become a drainage channel.

‘Is there a better campsite?’ I enquired.

‘No’ came the helpful reply

‘So, apa boleh buat?’ Some expressions do not translate easily, the best I can come up with is somewhere between ‘what choice do we have?’ and ‘fuck it!’

As a concession we familiarise ourselves with the emergency exit route to a howf under the boulder.

From here it is a relatively simple matter to descend the fixed ladders and ropes of Bowen’s Route and rejoin the tourist path. We would be back at Park HQ the following afternoon. With the time pressure lifted we relaxed to cook up a feast. Feeling mighty full we were astonished to see Jasirin and Girul eat about twice the volume of rice that we had consumed, plus a side order of noodles. At breakfast we were even more surprised and mildly disgusted to see them making the left over cold rice palatable with the addition of hot coffee!

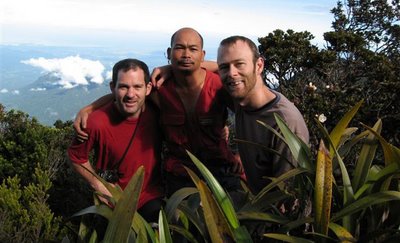

Their culinary habits aside, it was a pleasure to be on the mountain with such enthusiastic guides. As Graeme observed it was obvious that they too were highly motivated to do this route. For Graeme, I felt a little paranoid that I had chucked him in at the deep end but he remained steadfast throughout. I think there was a big turning point for everyone once we crossed the Penataran River, from that point on the option of retreat became unappealing. The moment at which you commit to a route is always difficult to pin down, but once you’ve crossed that line the doubts subside and everything falls into place.

All photos by I Hall and AG Shepherd. For a complete set of Ian’s photos click here

All photos by I Hall and AG Shepherd. For a complete set of Ian’s photos click here

Related Posts

%RELATEDPOSTS%