Building for Conservation

This article appeared in the community section of IB World Magazine, the official magazine of the International Baccalaureate® (IB) September 2012 edition.

View PDF

Related posts

%RELATEDPOSTS%

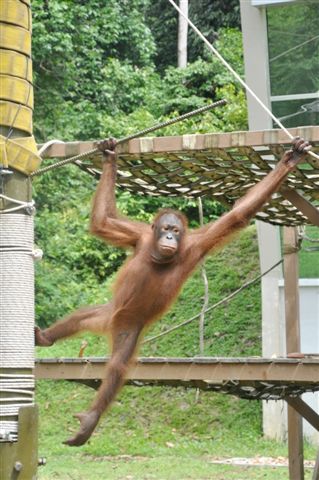

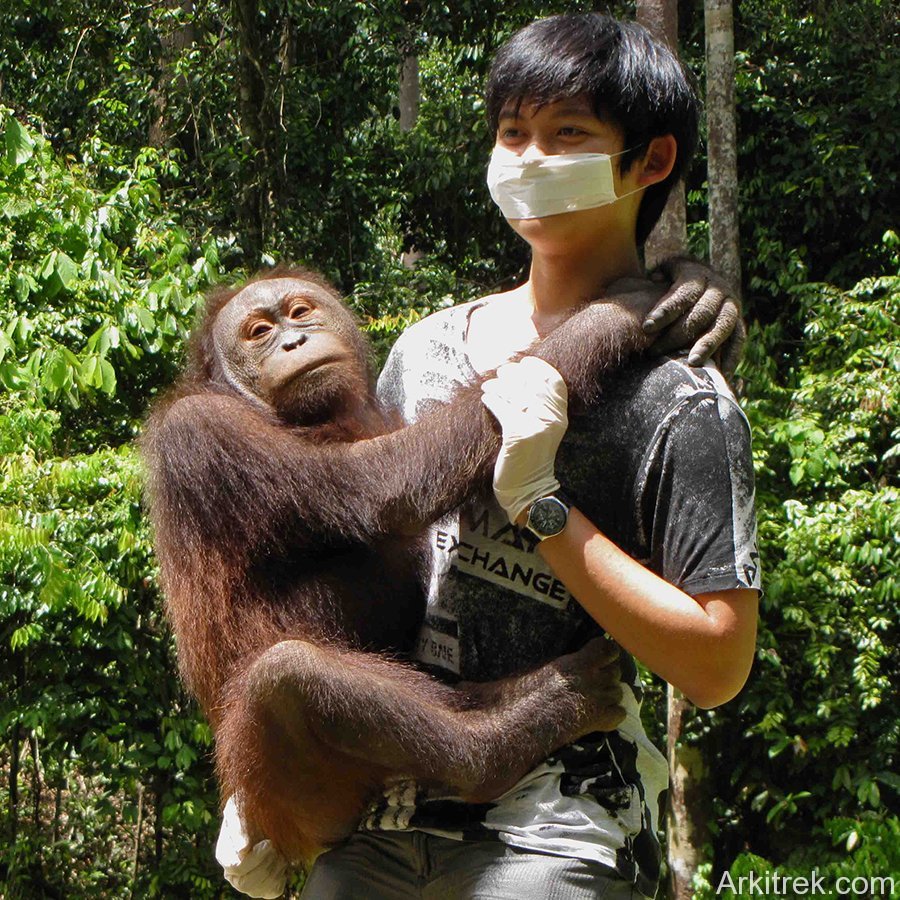

The Orang Utans and the Students

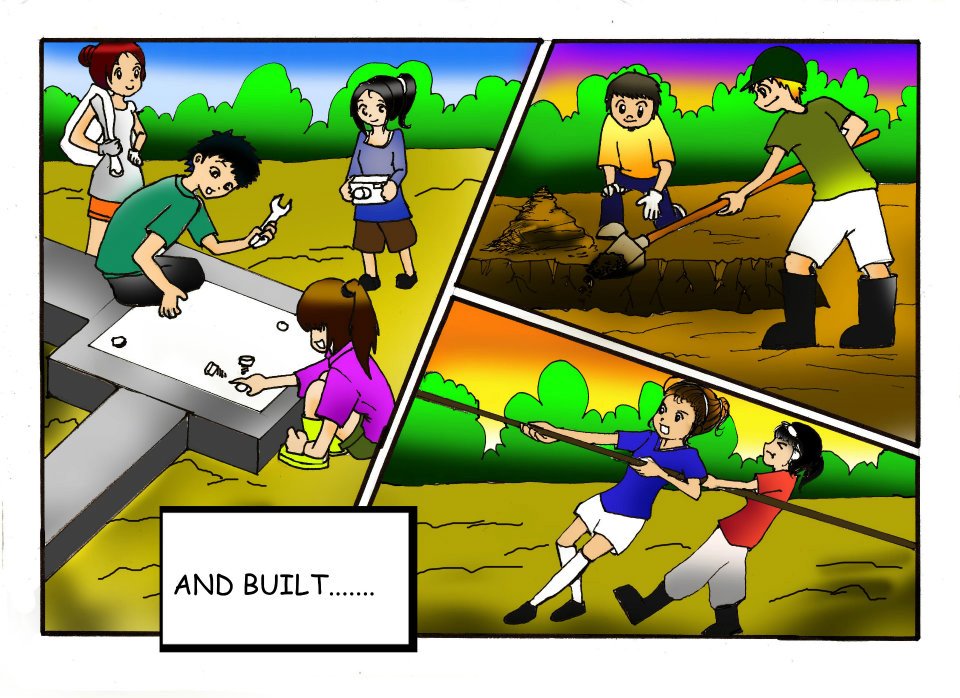

In the still-hot, late afternoon sun, the 6th form students are quiet, tense even, paying attention to the rope in their hands. They watch as 200kg pole moves higher and higher, as the end of it finally leaves the ground, wobbles and is then steadied, hanging from the rust red pyramid of scaffolding poles, swaying slightly 7m into the air. This was the final stage of a years worth of work. It was the culmination of months of research, long nights of design discussion and development, weekends of device testing, days spent shovelling gravel and mixing concrete.

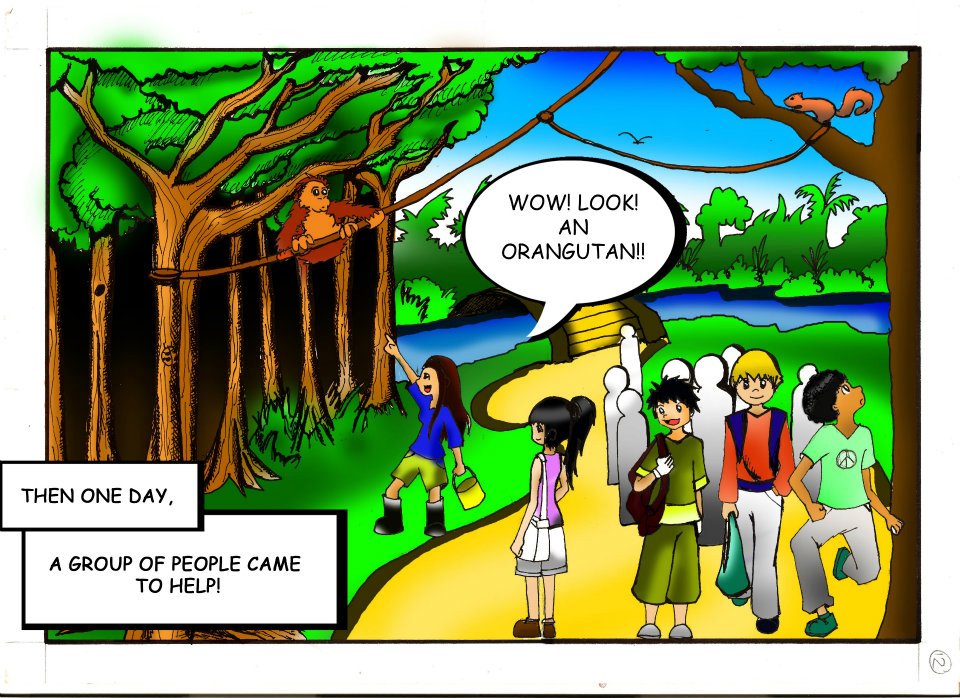

The idea came from introducing two parties that had approached us – the Sepilok Orang Utan Rehabilitation Centre (SOURC) wanted a more imaginative design for their training area for the 3-5 year old orang utans, and Richard Strange, a maths teacher at the Jeradong International School, Brunei, was looking for a project that would introduce architecture to his students. Richard saw architecture as a discipline that would draw on many of the skills that the students were learning in theory at school, such as mathematics, sciences, arts and business studies; and amalgamate them in one practical project. His vision was for a project that would involve all the core skills, develop them and give the students an experience to build on.

At first the students were surprised that they were being asked to tackle a project of this scale:

This is a project that is unique to Borneo, and it’s amazing that we as school kids can contribute towards it. Plus, it’s been really fun and amazingly rewarding!

Natasha Thottacherry

Never have I experienced a project that challenges me both mentally and physically, but still feels so fulfilling at the end of the day. I’m really excited to see the outcome after all of this.

Yee Ling Leong

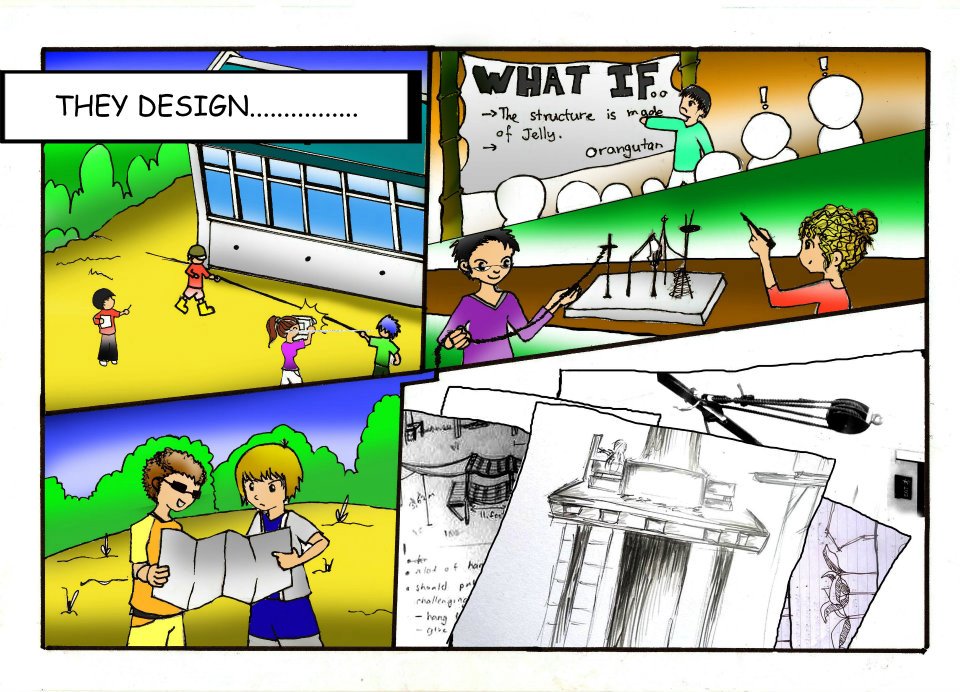

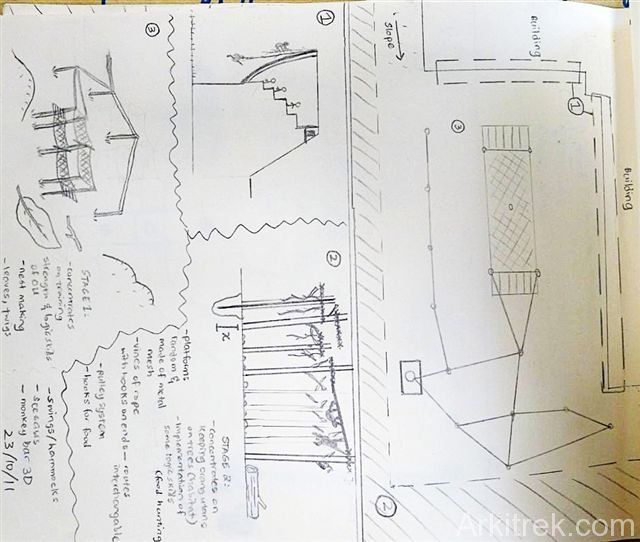

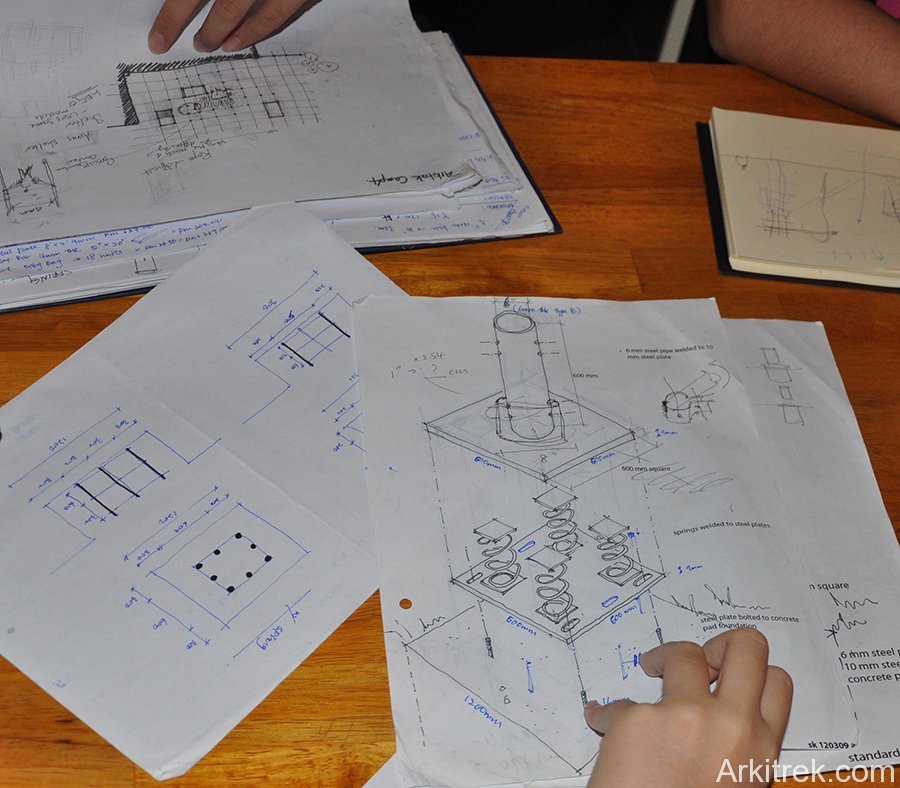

Over the course of the year many skills have been applied. In the early stages, when the site was first being surveyed, maths and physics lessons came to life as the measurements were taken, existing structures were triangulated and the height of trees were measured. The students displayed great professionalism and inter-personal skills as they interviewed the centre managers, trainers and scientists involved in rehabilitation. They applied analytical skills to precedents of other orang utan centres and then integrated the main concepts of these designs with their own opinions of what would make a successful training centre. During the design process, the students worked well together in groups and came up with a design that was collective, with no sole ownership. Although at first most were reluctant to sketch and everyone was shy to let anyone else see their sketch books, soon they had more confidence and were learning to communicate their ideas through scribbled cartoons. Models were built, scale had to be considered as well as material selection and construction. They presented their ideas with clarity to the Ranger in Change at Sepliok and gained for themselves a lot of respect.

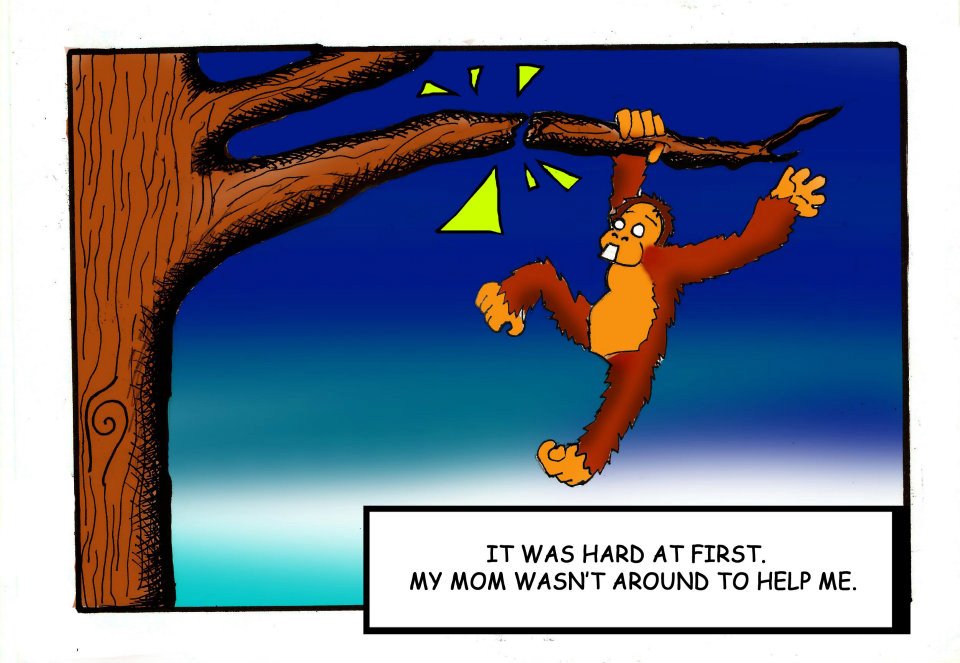

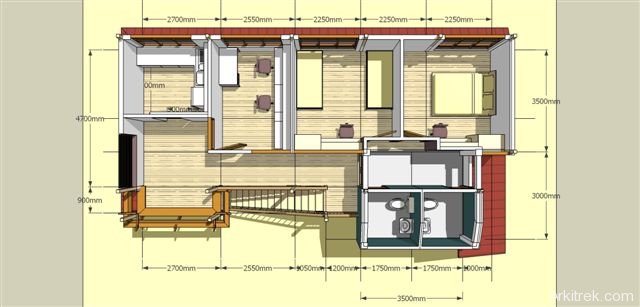

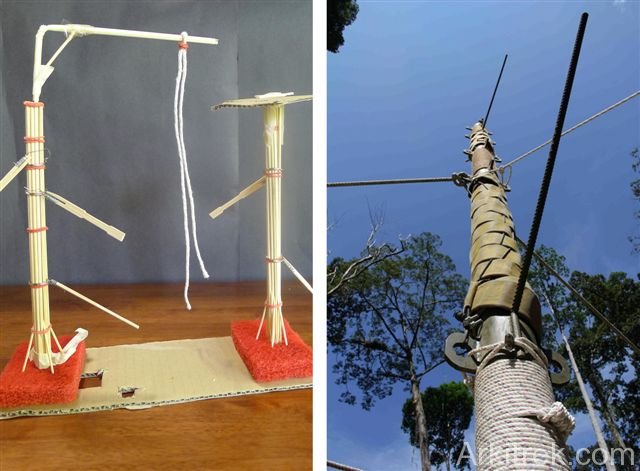

In the process of design 5 main areas were identified as being important to address in the training centre. The facility had to give a lot of variety to keep the intelligent orang utans interested. It had to teach them to climb high, to move from tree to tree, to forage for food and to build nests. In the final design 3 of these things are accomplished and ideas were left behind for further groups to develop the other 2 areas. Very quickly the desire to mimic the forest as much as possible was obvious. Branches were developed that were wobbly, that rotated 360 degrees to make them variable and branches that could be interchanged to be either tree branches, or in the future, poles that hold platforms or nest building devices. Also developed was a whole ‘tree’ that was sprung and would teach orang utans to balance their own weight against that of unstable trees. The final construction called for a lot of development and ideas testing before it could move to site. In this vein, car springs were tested for their ‘springyness’ and to see if they had a breaking point. Ideas were developed and fabricators were consulted to create pivots with ball bearings that would allow branches to rotate. A lot of work also went into developing pulley systems that would allow platforms of variable height and also food to be hoisted to the top of the poles. Unfortunately, this idea wasn’t carried through to the final design but will hopefully be developed again later.

As well as working on the construction of poles and devices to train the orang utans, the students got involved in working out the bill of quantities for the construction project and the budget required. They fundraised to cover the costs of the project. They also raised awareness in their school community about the project and applied for sponsorship from corporations.

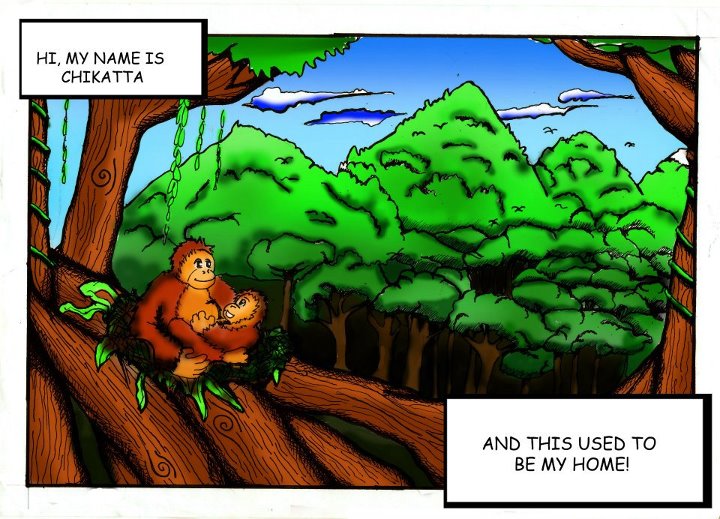

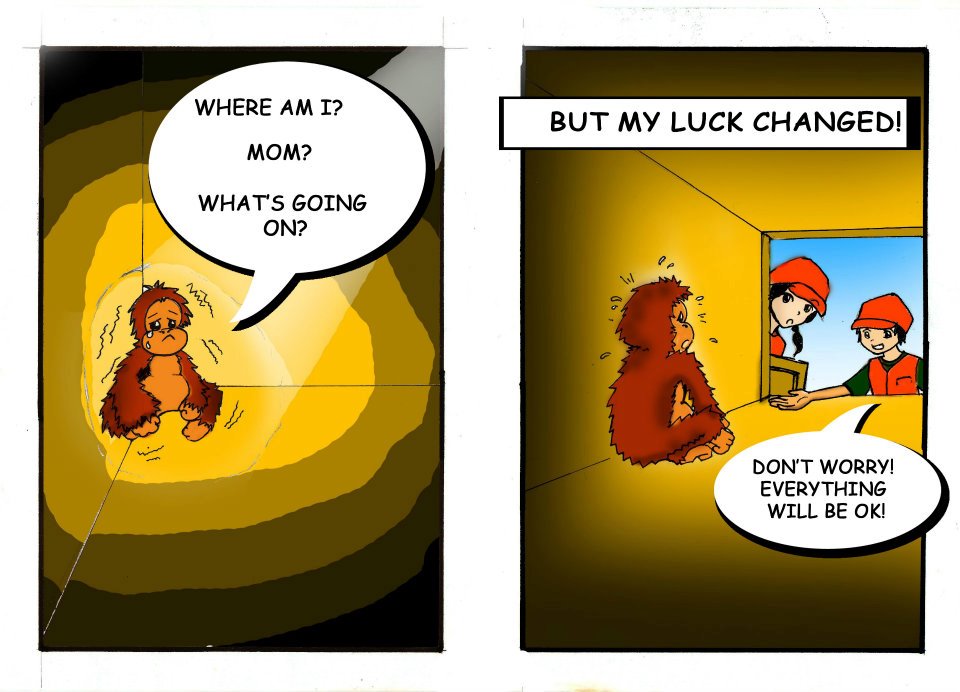

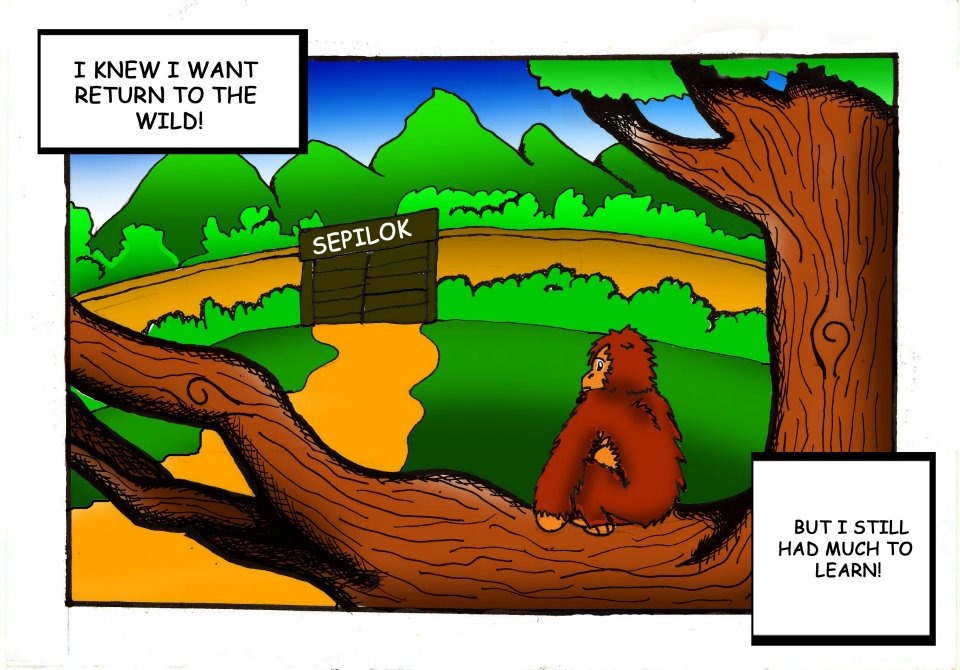

Now, in the final stage of construction, the students are drawing on management skills to arrange themselves to accomplish the final tasks we have set them. The construction side is actually easy – most of the decisions have now been made and now its only a matter of assembling the various parts. However, it’s also important that a record is left of the work completed and the ideas generated, both for the staff working at Sepilok as well as the tourists that will be given access to the site. To this end a variety of interpretation is being put together, including an operating manual for the staff and a cartoon strip that at one level gives the story of an orang utan at Sepilok but also adds a level of information that gives tourist an awareness of the bigger problem and how they can help conservation as a whole. In addition, there is also a short film in production that tells the students’ experiences at Sepilok. Results will be posted in due course.

This was a project that Arkitrek were excited to be involved in as facilitators, but it was also somewhat unnerving. So far our workshops have been with university students, teaching architecture is a different matter. However, the students easily won us over with their hard work, willingness to learn and enthusiasm for the project. They have been really determined and committed and Arktirek is proud to be associated with them. We look forward to many more similar projects in the future.

Related posts

%RELATEDPOSTS%

Sungai Ulu Danum Research Station

Photos by Ian Hall and Serena Lamb

The forest around Borneo Rainforest Lodge (BRL) is home to an extraordinarily high density of orang-utans. More than 30 individuals are being monitored in a research program lead by the Wildlife Research Center (WRC) of Kyoto University. Wild orang-utans are very good for nature tourism and I reckon that during a three night stay at the Lodge there is an even chance of seeing at least one of those fellas.

The WRC research program now has a new purpose built home at BRL thanks to collaboration between Yayasan Sabah, University Malaysia Sabah and Kyoto University. The Sungai Ulu Danum Research Station was opened recently by Dr Waidi Sinun, director of the Conservation and Environmental Management division of Yayasan Sabah.

Nature tourism and ecological research do not always sit happily together. This is why the Danum Valley Conservation Area Management Plan separates researchers at the Danum Valley Field Centre from tourists at BRL, the fear being that tourists may scare away animals under study or trample research plots.

In fact far from scaring away animals, the benign presence of tourists at BRL has resulted in the animals becoming habituated to people. You can now regularly see bornean gibbons, red leaf monkeys, crested fireback pheasants, dwarf kingfishers, mouse deer, sambar deer, clouded leopard, flying lemur and of course orang utan, all without stepping off your balcony.

If you’re not lucky enough to see an orang-utan from the balcony then the presence of the research program means that someone knows where the orang-utans are most of the time. The researchers are studying the ecology and behaviour of orang-utans without direct intervention. In other words the apes are not captured or collared; data is gathered by following them and observing their behaviour and collecting any samples that they might drop.

The presence of tourists does not interrupt this process and it means that more people get to see ecological science at work and learn about this great ape first hand in its forest home. Arkitrek is proud to have designed the research station and hopes that the researchers and research assistants will be comfortable there for the duration of their field work.

Little & Large of the Orchid World

Text by Ian Hall

Photos by Ian Hall, Serena Lamb and Eyen Khoo

Horticulturalist and orchid expert Tony Lamb has thrown down the gauntlet to describe the world’s largest orchid. The Tiger Orchid, Grammatophyllum speciosum is the undisputed king of the orchid world but where is the largest specimen to be found in the wild? The question was raised during a walk along the access road to Borneo Rainforest Lodge (BRL) in the Danum Valley Conservation Area in Sabah.

The orchid that caused Tony to stop in his tracks was so big that despite walking past it every day I had not even realised that it was an orchid. There is only so much you can teach yourself about the countless species in the web of life of a tropical rainforest. It as a treat to be in the company of Tony Lamb and Anthea Phillipps who knew far more than me.

The orchid that caused Tony to stop in his tracks was so big that despite walking past it every day I had not even realised that it was an orchid. There is only so much you can teach yourself about the countless species in the web of life of a tropical rainforest. It as a treat to be in the company of Tony Lamb and Anthea Phillipps who knew far more than me.

We were at BRL to assess the nature interpretive information that is presented to guests not lucky enough to have such knowledgeable guides. Through audio visual and textual media we can give an insight into the wonders of plant / animal interactions and other ecosystem functions, plus of course trivia such as; how big is the world’s largest orchid?

To answer this question Tony recruited some tree climbing botanists from the Sabah Forestry Department to physically measure the BRL Tiger Orchid. At 30m above the ground this was no easy task but climber Jeisin Jumian counted 90 live pseudobulbs up to 3.3m in length with leaves extending a further 0.3m.

Back at the Lodge we watched one of the plant/animal interactions for which BRL is famous. An old male orang-utan munching tarap fruit next to the veranda. All the guests were ecstatic to see a wild orang utan so close and after lively debate Tony and Anthea agreed on the species of tarap being eated as Artocarpus rigidans.

Back at the Lodge we watched one of the plant/animal interactions for which BRL is famous. An old male orang-utan munching tarap fruit next to the veranda. All the guests were ecstatic to see a wild orang utan so close and after lively debate Tony and Anthea agreed on the species of tarap being eated as Artocarpus rigidans.

No trip to BRL would be complete without traversing the canopy walkway suspended 20m above ground between emergent dipterocarp and mengaris trees. The walkway is at barely half the height of these enormous trees but sensationally within the rainforest canopy.

Canopy science is at the frontline of ecological research both because it is hard to get to and because this is where most of the primary productivity of the rainforest occurs. Last year a new species of bird was described from the BRL canopy walkway. That one of the most intensely observed bits of canopy in Sabah can still yield new vertebrate species hints at how much there is still to learn.

Hot on the heels of canopy science is canopy tourism. Being in the canopy is a dramatic experience that allows your imagination to take flight. It is a vertical super natural world where the trees provide a structure to be inhabited by plant families like ginger, pandanus, lichopodium, aeroids, ferns, orchids, mosses and the animals that they are interdependent with.

To recognise and know the names of some of these living things allows us to talk about them and share our observations. This becomes knowledge which if it can be imparted to tourists will greatly enhance their experience. After all, one of the main points of travel is so that you can go back home and brag about what you have seen and done.

On the last platform of the canopy walkway, Tony paused to pick up what I thought was just a leaf. It turned out to be an entire plant fallen from the canopy, an orchid of unknown species hardly bigger than a thumb nail and with a flower stalk barely 40mm long, bearing flowers 1mm in diameter. A contender for world’s smallest orchid he reckoned.

By this stage my mind could cope with no more latin names so we retired to the bar where I was very pleased to hear Tony ordering a double gin. ‘For scientific purposes’ he winked and poured it into a specimen jar containing the tiny orchid.

Related posts

%RELATEDPOSTS%