BFM: Implementing a Sustainable Design

Ian Hall, founder of Arkitrek talks to BFM presenter Freda Lui about the Arkitrek Camp and his philosophy of working responsibly in Malaysia’s natural areas and building capacity for rural communities in Borneo to implement a sustainable design.

Mantanani Basketcases

Text and photos by Ian Hall

Our Kindergarten on Mantanani Island has come on a treat these last 4 months thanks to the dedication of our Volunteer Michelle Martin and her team from Camp Borneo and the Mantanani community. We’re just about to get the roof superstructure up and here is Michelle posing with a fine set of dwangs on her last day on the island.

The next stage is to put the roof on and for this Michelle has risen to the challenge of communicating structural principles of a ‘collar rafter’ and the relative merits of varying roof pitches to our doubting master-craftsman Albi. Apparently you do it by stacking cards. In the end though, language wasn’t the issue. What Albi was too proud to tell anyone is that he is scared of heights and no amount of cajoling and scaffolding would induce him up there to fix the rafters.

After the roof we need to sort out the cladding. For this we are adapting panels from a traditional weaving technique normally used for making rice threshing mats. In other words, our building will be a basketcase, or is that the fate for volunteers marooned on the island? Mind you, Michelle was a little crazy to get involved in the first place. She’s had to keep hundreds of school children busy painting, nailing, sawing, digging and basketweaving for three months.

The weaving was another challenge of communication, this time brokered by Arkitrek’s volunteer coordinator, Hasmartina. She was initially quoted MYR70 per piece for something similar to a rice threshing mat that you can buy from the roadside stall for less than MYR20. What we ended up with was buying the raw materials and paying the weaving ladies MYR30 per day to go to Mantanani to teach weaving to the school volunteers.

This was a great solution because the volunteers get more engagement with the locals and the locals get a paid jolly and the chance to diversify their enterprise. There were some politics to decide which ladies got to go on the jolly but it was all sorted out amicably.

Once on the Island we learned that the bamboo we had been delivered was the wrong type. Sarah is pictured on the left with some of the right type of bamboo; it is green and therefore easy to strip plus the culms are well spaced so you get a good length to weave with without a culm joint. Even with the right kind of bamboo, Michelle and Camp Manager, Aida found that cuts from the sharp shavings placed a heavy toll on the camp sticking plaster stocks, even when wearing protective gloves.

Once on the Island we learned that the bamboo we had been delivered was the wrong type. Sarah is pictured on the left with some of the right type of bamboo; it is green and therefore easy to strip plus the culms are well spaced so you get a good length to weave with without a culm joint. Even with the right kind of bamboo, Michelle and Camp Manager, Aida found that cuts from the sharp shavings placed a heavy toll on the camp sticking plaster stocks, even when wearing protective gloves.

Our team produced 25 finished cladding panels, so that leaves only 225 to go which we’ll either pay the weaving ladies to do themselves or get them back to teach. The challenge remaining for a future Arkitrek Volunteer is to figure out how to arrange and fix the finished panels on the walls of the kindergarten. Some people call this ‘the design process’ and others call it ‘making it up as we go along’.

It was to her great credit that for all that was on her plate during her stay on Mantanani, Michelle succeeded to maintain the integrity of our design, stay friends with everyone and keep her sanity…

….I don’t know how she managed it:)

Bamboo shavings after weaving work.

Some finished cladding panels stacked up at Camp Mantanani

Related posts

%RELATEDPOSTS%

The Star: Designs that matter

The Star, Malaysia

Saturday July 16, 2011

Designs that matter

By LEONG SIOK HUI

Read the original article

A team of budding architects and design professionals picks up construction know-how and ruminates on why design matters at a design-and-build camp in Sabah.

After seven years of slogging in architecture school, followed by 2½ years of designing building after building, David Thomas Arnott was on the verge of burning out.

“You spend so much time in university working on amazing projects. Then you start working and get caught up in the rat race. I wanted to do something meaningful, on a smaller scale, but with instant impact,” said Arnott, 26, who works with an Edinburgh-based firm.

So in May this year, Arnott signed up for a three-week architectural camp on Mantanani island, off the northwest coast of Sabah. Arnott was one of five paid participants taking part in Arkitrek Camp 2011. Open to architecture students and design professionals, the Camp provides participants with a real client and a very real design brief.

Over 21 days, participants are expected to design and construct a building from scratch.

“The idea of the camp is to bridge the gap between theory and practice. In most architecture schools, students never get a chance to build a single building,” explained UK-registered architect Ian Hall, the brain behind the Camp.

Hall has been practising architecture in Malaysia since 2004. His design consultancy, Arkitrek Sdn Bhd, tends to focus on rural projects and has worked with clients like Borneo Rainforest Lodge in Danum Valley and Bornean Sun Bear Conservation Centre near Sandakan.

“The Camp reflects Arkitrek’s philosophy of working responsibly in natural areas and building capacity for rural communities to implement a sustainable design,” explained Hall, who added that urban architecture didn’t cut it for him.

Will Smith and Teng Quan Zee putting up the first of the roof rafters sawn from driftwood.

Will Smith and Teng Quan Zee putting up the first of the roof rafters sawn from driftwood.

The context

At the inaugural Camp this year, the client was UK-based volunteer travel organisation, Camps International (CI). CI’s design brief was for a marine learning centre that doubled up as play area and community meeting spot for 900 Mantanani inhabitants. The idea was to convince the islanders of the importance of preserving the environment.

“Our ultimate aim is for the community to be stewards of their own marine environment and to generate income for the locals to raise their standard of living,” said Melanie Chu, CI’s Camp Borneo general manager.

The Arkitrekkers (as participants are called) were mostly design students and graduates from Malaysia, the US and the UK.

“This type of project, where you solve community problems via architecture, is where I feel I can really help people through design,” said participant Chew Pui Cheng of Petaling Jaya.

Chew, 21, completed her architecture diploma at Taylor’s University and is continuing her studies in Scotland this September.

“You also get to work with design students from various countries,” she said.

Led by camp facilitators Sarah Greenlees of the UK and Daniele Elian Cohen of the US, the team started out by familiarising themselves with the vernacular building styles of Kota Kinabalu, then interviewing CI’s Mantanani camp manager Aida Rahman and the village headman, Albi Alad, before coming up with a design.

They settled on a building with a mono-pitched roof, fashioned mostly from driftwood and sawn timber.

More than just a glorified hut, the structure would boast 4.5m high driftwood columns. Additional features included a deck overlooking the sea, openings for cross-ventilation and a wall made from recycled plastic bottles.

Driftwood of various shapes and sizes would be stacked up to make a wall to show off their beauty.

The team spent the first few days looking for massive driftwood from the sea.

“Thanks to the roof sheets sponsored by Onduline, the total budget only came to RM6,000, including tools,” said Hall.

Since the building was to be strategically located between the two villages on the island, the team incorporated a pathway that sliced through it.

“The idea is to make a thoroughfare for the school kids on their way to school,” explained Greenlees.

A counter would be used as a shop for selling knick-knacks, and there were provisions for living space for the community to hang out in.

On top of what they could complete within the three weeks, the team also decided to leave behind a set of drawings that would allow future Arkitrekkers and CI volunteers to add to their building.

Founder of design firm, Arkitrek Sdn Bhd and Arkitrek Camp, Ian Hall.

Hands-on learning

Over the weeks, the team had to return to the drawing boards several times to make adjustments as required.

“When you study architecture, you fall into a trap where you do a drawing and it gets sent away. Building with our bare hands allows us to understand how things are built and makes us a much more well-rounded architect,” Arnott said.

He had initially worried that the camp might be too theoretical and that the design discussions would turn into ego fights. But that never happened.

“It’s been great fun on site! I’m impressed because when you look at the size of the huge columns, it’s almost medieval because we don’t have a crane and we did everything by hand,” grinned Arnott.

One participant, Michelle Louise Martin, said she studied construction for two years before university but she only really learned the nuts and bolts of construction at the Camp.

“On previous site visits, if I didn’t like something, I’d say to the contractor, ‘Change that please!’ Now that I know what they have to go through, I’ll be nicer next time,” chuckled the 23-year-old who worked as a conservation architect for three years whilst finishing her degree.

Martin admitted she was homesick and suffered from culture shock in her first week here.

“The heat, the squatting toilet and the food, going from meat and veggies to rice and noodles all the time … I struggled with all that at first,” the soft-spoken Martin revealed.

It was her first time away from home alone, and not having Internet or mobile phone reception on the island didn’t help.

“I wish I could just speak to my mum over the phone. But everyone’s been absolutely amazing. We’re getting on great and laughing a lot,” she added.

A senior at the University of Oregon, William Frederick Smith snuck out of college in the middle of spring semester to join the Camp. He said he liked working with reclaimed materials and thinking about environmental impact.

“My university has always been a green-oriented school but we talk about sustainable design on a big scale, like solar technology,” said Smith, 21.

“Here, we do simple but necessary things like rainwater harvesting and see it being applied.”

The Arkitrekkers got a real kick out of collaborating with locals like Albi and his brother, Hashim, who handled the chainsaw and dished out tips on using local materials in the best possible way.

“I’m impressed by how focused and motivated the team is,” said Albi, 57, a full-time CI employee who builds houses and boats for a living.

“They pick up things fast, and I actually learned a lot from them despite my 20-year experience in construction.”

The completed structure will be used as a marine awareness centre and a community space for Mantanani islanders.

The completed structure will be used as a marine awareness centre and a community space for Mantanani islanders.

Epiphanies

Like most of the Arkitrekkers, Smith experienced his own design epiphany of sorts.

“I realised you can make good architecture without having to be a stressed-out desk monkey. I could either follow the profession, get huge urban projects and solve urban problems. Or step outside the system, do smaller community projects and forge personal relationships with clients that result in meaningful projects that stay with you, regardless of what you started or ended with,” Smith said.

“Yes, after this Camp, I believe architecture should not just be about providing space, but making that space important to its users and bringing together communities,” Martin chipped in.

By the end of the three weeks, the team had completed over 90% of the building. The learning centre is now fully functional except it still requires a counter for the shop and a lockable store.

For Chew, the Camp left lasting memories.

“The unforgettable moments – when the local kids worked alongside us, taking turns to bore holes, putting up the recycled bottle wall, collecting sand and sawing wood, or when they dived into the huge hammock and collapsed into a pile of giggles, or clambered all over the unfinished driftwood wall. Our building has worked its magic,” she enthused.

Arnott said the Camp had reinvigorated his passion for architecture.

“The team’s passion for architecture is infectious. I’m definitely putting more energy into my design and not giving up so easily,” Arnott said in an e-mail two days after returning to Scotland.

Smith summed it up perfectly: the Camp “is a down-to-earth project and process, a group of people from around the world, a beautiful context to explore.”

Arkitrek Camp2 will be held from Jan 4 to Feb 4, 2012 on Mantanani Island, Sabah. For details, check: https://arkitrek.com/arkitrek-camp/

Batu Batu Reef & Islands Study Centre

Text: by Ian Hall

Photos: by Ian Hall and Fauzan Aris

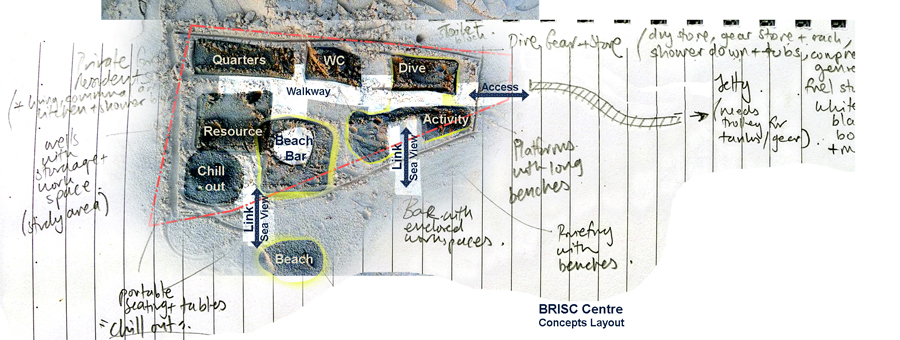

Pulah Babi Tengah (Middle Pig Island!) off the coast of Johor, Malaysia used to be a refugee camp run by UNHCR back in the 70’s. I’m not sure how idyllic a refugee camp could be but former interns, mostly Vietnamese, now Australian, seem to have fond recollections of the place. Stepping out of the glare of the sun and into the cool shade of the casaurina grove, you don’t have to look far to find relics of the refugee camp. The design team for the Batu Batu Reef and Island Study Centre (BRISC) pause to spread out their kit atop a concrete well, one of a network of wells which supplied water to the island’s former transient residents.

The BRISC big idea is to link beach tourism with marine conservation, in this case facilitated by a partnership between Batu Batu Resort and Wild Asia. This partnership will inspire others to adopt principles of responsible tourism. After all, the tourism product in this case is crystal clear sea, clean beaches and abundant marine life. It makes good sense to protect this resource.

The BRISC big idea is to link beach tourism with marine conservation, in this case facilitated by a partnership between Batu Batu Resort and Wild Asia. This partnership will inspire others to adopt principles of responsible tourism. After all, the tourism product in this case is crystal clear sea, clean beaches and abundant marine life. It makes good sense to protect this resource.

Swatting troublesome mosquitoes and sand flies we debate where the living, working, chilling and dive centre functions of the BRISC should go. Someone told me once that casaurinas are colonial trees, as in, they grow in colonies. Their encircling trunks enclose a soft floor of needles, a shady and natural gathering place. Two such groves form the starting point for our site layout design concepts.

There will be a beach bar, naturally, on the beach. It will close shortly after sunset and the lights turned down to give those turtles a chance to navigate without distraction. There’s a gap between the casaurina groves which is an obvious place to connect the beach bar with the living and working areas under the trees.

Our intern Fauzan Aris, an architecture graduate from University of Malaya, is measuring the depth of a UNHCR well with a tape measure. Dr Reza Azmi, founder of Wild Asia is dangling a water sampler into the same well to test it’s salinity amongst other things. I’m looking at an Asian Brown Flycatcher through my binoculars.

There is a cluster of three wells on our site and the BRISC living and working areas will be built around them. The thick screen of vegetation at the beach edge will be retained. Those thick waxy leaves of Barringtonia and Terminalia trees are adept at retaining water in this harsh environment. They’re also pretty handy at providing shade and screening.

Other areas of the site are characterised by clumps of hibiscus and the leaning knobbly trunks of a leguminous tree species. It is in the legumes that I am watching the flycatcher and from their canopy comes the constant cheep-cheep of sun birds and flowerpeckers. Using illustrations in sketchbooks perched on the well covers we discuss how to retain this ecosystem.

Some trees will have to go of course but we can move the buildings around to protect and integrate larger trees and clumps of trees. We can also translocate the forest floor by about 6m vertically to the green roofs of the BRISC living, working and dive centre areas. Even the beach bar, poking out over the sand, can have a green roof. They’re very tenacious those casaurina and terminalia saplings. Can grow anywhere, although on the beach bar roof they may need to be kept trimmed so as not to overgrow the photo-voltaic panels.

Slap, slap, splat….scratch, scratch. Sand flies win and we adjourn to the beach now that the sun is going down. Our minds are buzzing and architect Leong Seng Kheong engages Reza in a furious sand etcha-sketch one-on-one battle. A sweep of the hand erases the previous sketch and simultaneously prepares a clean canvas for the next. Fingers etch out blobs and squares and lines and voila! A site layout design concept.

When BRISC is up and running the day to day activities will include monitoring changes in natural resources, including biodiversity. This data will provide evidence for how well the tourism operation is safeguarding the environment and allow it to adjust appropriately. The presence of naturalists and environmental science type fellas on the island will add value to the tourists’ experience and understanding of their impacts on the environment.

The presence of the dive centre will allow these studies to focus on the marine environment, although hopefully there will still be space for those who prefer binoculars to snorkel masks.

Related posts

%RELATEDPOSTS%