Padi, Pigs & Chasing The Frog

By Oliver Wilson

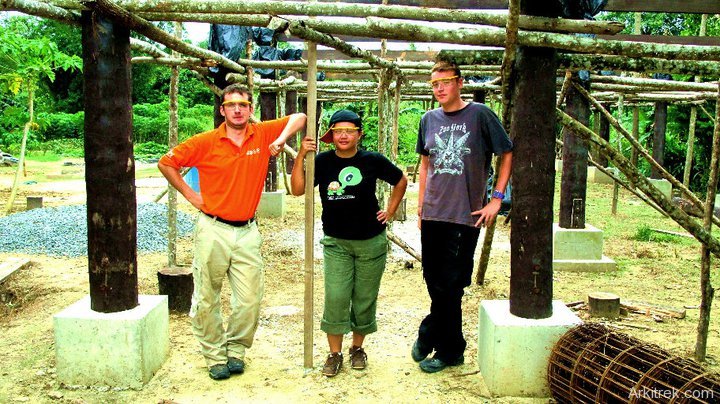

Ed: Oliver is the second Arkitrek Intern to work with Camps International in Sabah. His role was to detail design and construction manage a community kindergarten project. He worked with local craftsmen and volunteer tourists to keep the project on track and maintain high standards. You can see some of Oliver’s work here. A big challenge for Oliver, as with all Interns who come to work in Sabah, is to adapt to the local culture. Allow Oliver to explain

Before I came to Tinangol, I wasn’t sure what to expect, but somewhere in my mind I had pictured Sabah mainly as one of the ‘softer’ parts of the Islamic country that is Malaysia, but any place where you are first greeted with a fresh coconut followed by masses of barbequed fish and a certain amount of locally made alcohol, I figured I was in for an eventful three months.

With my predecessor, Eoghan Hoare, already setting the pace as the last Irishman to work and live with The Rungus, and with the many epic tales of his presence on my first night, I realised my first impressions were a mild and underestimated expectation of what was to come.

The task to be undertaken was to further develop designs and bio-composite materials for the Community Hall and Kindergarten which had already been started on site, following on with the idea that using local materials would be the best approach. So far, I figure the best ‘research and development’ I’ve managed to conduct has been a result of a blind backwards dive into the social goings on that so frequently occur around Kampung Tinangol.

On my first days on site, in the sapping heat, I was continuously presented with papaya, rambutan, coconuts and countless other bounties that are in abundance around the village. Also, I was given an introduction to Tapioca which in the past has served as one of the main staples to The Rungus. The conversation led to how the growing of this sweet potato around The Kudat area has declined in recent years, with hill Padi now being the most abundant, and as I was about to find out, probably the most important crop in the area. Not only does it provide the food staple, but also provides the basis for much of the villages merry-making and celebration – montauku or rice wine.

When together with other Arkitrek Interns Daniele and Chris we where invited to join the community in planting the padi, I had pictures in my mind of long hot days toiling in six inches of water with my back bent like a horseshoe as I had often seen people do on TV, as I was later to learn this was far from the experience I was going to have! By the time We had reached the jungle clearing in the early morning I had probably already sweated close to my own body weight, and looking at the men and women making their way back and forth the hillside I wondered how in the hell these people could wear so many clothes!!

Tasks when planting hill padi generally are separated by gender, then men moving along in a neat row piercing the ground continuously with pointed staffs, while the women (of whom at first we were merrily joined with) follow behind skilfully flicking 4-5 grains from waist height into the pre prepared pin holes in the ground. The women remained upright the whole time, with three ‘orang putih’ (white people) strugged to follow with distinct horseshoe shapes desperately trying to master the aiming technique.

Shortly before 12 o’clock, we were confident that we had achieved some proficiency in what we were doing, and just in time as announcement was made that it was lunchtime. What nobody told us though, was that the days work had already been finished, our experience for real was now about to begin.

The small breaktime hut became surrounded with masses of local people, bringing with them vast amounts of all varieties of fish; large and small, seafood & vegetables I never knew existed, wild pig and of course, rice. Banana leaves were laid on the ground to eat from, fallen coconut posts were arranged to form communal seating, small fires were lit around us to ward off insects and cook the food, and the banterful feasting began.

Also lurking in jute bags was a copious amount of whiskey, gin, ‘island mixer’ and yes, the ever present rice wine. The events that followed are a bit blurry, but I know at least I survived my first ‘after planting’ party. On my second, I recall only that after having purged something in the region of 12 hours from my long term memory I awoke in the communal veranda of one of the village longhouses, ravaged by mosquitoes and being asked by a total stranger whether I wanted Chivas Regal or Johnny Walker for breakfast. I somewhat less than gracefully declined.

I was later to learn that occasions like this would become common in my time in Tinangol as the people here rarely need an excuse to celebrate. Questions regarding the fact that the locals tend to keep their Christmas decorations up all year round is often answered by the phrase “Every day is Christmas in Tinangol”, and it’s not often that you won’t see these folks with a massive grin or their face.

However with the local economy being based mainly on agriculture, money certainly is not the carrier of many of the peoples’ day to day contentment. The local people are quick to make use of everything that grows and can be produced around them, much of which is also shared communally. For example, once while a few of us were having a small party to welcome a new volunteer, a chicken was brought into the house and swiftly made into soup to share around. Upon thanking Matusin for the donation of his chicken, our gratitude was met with much laughter around the group, after which I was told: “Olly, I don’t think that chicken belonged to Matusin!”

Looking back at my time here it has to be said that every day has presented something new, each experience being very interesting and the majority of them highly comical. So if you know somebody who’s been really busy lately and is a bit stressed out, or maybe just takes life too seriously, send them here. These guys will sort them right out.

To start to thank individuals by name would leave a lot of people out, so to everybody I’ve worked with, eaten with, drank with, sung karaoke with, had drunken conversations with and especially the people that have fed, watered and put me up in the kindest hospitality, thanks folks, I’ve had a absolute ball and I hope to see you all again soon.

Rungus factsheet

• The young men in Tinangol are encouraged to spend much of their time chasing an enigmatic frog that lives in the forests around the village. This frog is meant to bring much fortune and happiness to whoever may catch one, but the older men in the village can reveal that its possession may have cost them a lot more of their patience than they previously thought.

• When The Japanese occupied Tinangol, an officer had the right to enter any home without invitation and demand anything that he wanted from the house, be it anything from a chicken to a shirt. The Rungus, however were totally indifferent to this behaviour, mainly because they had no idea what the soldiers were babbling on about.

• No man can consider himself to be truly Rungus until he has achieved the ability to sleep in any environment, however uncomfortable it may be.

• It is wrong to make fun of or laugh at an animal. This displeases the powers that be and can result in poor weather such as thunder and lightning.

• Monkeys can be very vengeful creatures. Once upon a time, the monkeys that lived in the forest were great friends with the Rungus People, who employed them from time to time to plant and harvest Maize in their gardens in turn for enough rice to sustain them. This arrangement went well for many years until the people one day were late to come feed the monkeys. The monkeys, in order to continue working took a little bit of maize to bide them over. When the people returned and scolded the monkeys for such an act of theft, they retreated to the forest and to this day whenever the people plant maize, it is stolen by the monkeys.

• Having to “buy the pig”. According to the village chief, the penalty for pre-marital goings-on in Tinangol is having to provide enough food and drink to sustain the whole community in one days partying. Needless to say this could prove to be very costly, If not a bit counter productive considering that ultimately bad behaviour results in a celebration.

Related posts