Additionality

Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) and carbon credits sound like a good idea but I’m not sure how much they benefit rainforest conservation.

Behind my suspicion lies a concept that I have been aware of for a while but only recently learned that it has a name – ‘additionality’.

It’s a new jargon term which hasn’t yet made it into the dictionary. In understanding what it means I was lucky to meet a chap called Mike Packer who patiently and concisely explained things to me.

Mike is the founder of a company called ArborCarb which specialises in ecosystem services certification so he should know about these things.

By Mike’s definition; additionality in the context of carbon finance is “when the carbon benefits of the project would not have happened if the project had not been implemented”.

In other words, carbon credits are relative to the ‘business as usual’ scenario.

Perverse Carbon Credits

If business as usual is conventional logging, then carbon emissions could be reduced, for example by switching to FSC certified logging. In the world of carbon finance, this reduction of potential emissions can be converted into a carbon credit for sale on international markets.

Although this helps make reduced impact logging more viable, it also creates the absurd possibility of carbon credits for logging primary forest.

On the other hand, additionality fails to provide economic incentive for rainforest conservation. If business as usual is conserving primary rainforests, then no carbon benefits can happen by sticking with rainforest conservation.

This defeats the purpose of PES if you consider that this purpose is to make trees worth more alive than dead. Intact ecosystems rather than degraded ones.

The only way that the current carbon market can value living trees is through Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD). Additionality is provided here because business as usual is deforestation or degradation.

This point is picked up in an article by Katoomba Group which says “Some argue that countries with low rates of deforestation should be rewarded to avoid creating a perverse incentive for these countries to increase deforestation in order to then qualify for REDD incentives. However, in order to maintain the environmental integrity of a REDD policy, credits can only be generated by additional reductions in emissions from deforestation, and these countries would have to be rewarded through other means.”

Biodiversity Conservation Certificates

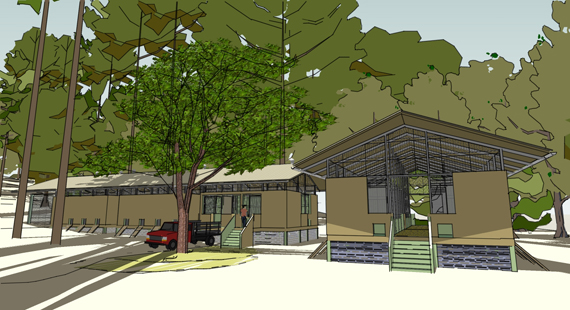

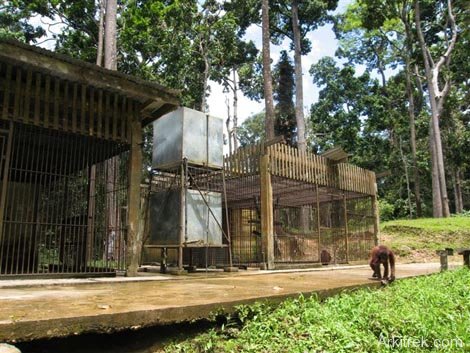

Other ecosystem services may also be dependent on additionality. For example the Malua Biobank.

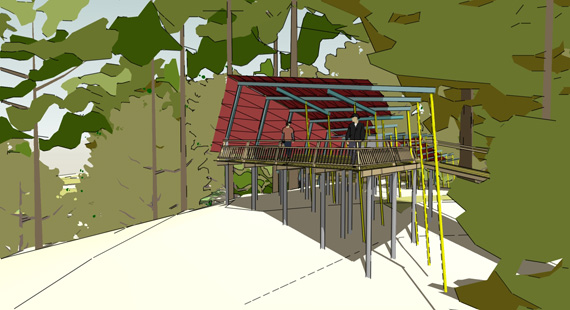

If this project did not go ahead the ‘business as usual’ scenario is leaving an area of degraded forest to recover naturally (over an unrealistic timeframe – economically) or converting it to plantation. By putting money into forest rehabilitation it is hoped that biodiversity can be restored more quickly – additionality.

The economic principles behind Malua Biobank are that investors will realise gains on the value of their certificates as biodiversity increases over time. This is still a voluntary market and sales are targeted mostly at companies that want to offset damage to ecosystems or simply want good environmental PR.

Of the criticisms of Malua Biobank:

One is that they are also planning to sell carbon certificates which may be seen by some as double selling the same resource.

Another is that it comes after a regime of environmentally disastrous logging practices. Third party investment in rehabilitation effectively excuses the logging companies from their obligation to pay the environmental cost of their operations.

The latter is also akin to double selling; you sell the logs, then you sell the biodiversity/carbon certificates for rehabilitation. Have your cake and eat it!

Scepticism about PES

My scepticism for PES, particulary carbon credits is that they don’t seem to provide enough incentive to avoid degrading the forest in the first place. Most are based on the assumption that deforestation or degradation has happened or is going to happen anyway.

I understand that this has been done in light of the reality of logging and plantations and the need to encourage these industries to be more sustainable. The result however could be losing sight of the fundamental principle of conserving forest for the benefit that it provides.

The baseline has been shifted so that PES are generated in relation to destruction rather than conservation.

The result of this baseline shift is a scenario in which a forest is being considered for REDD, which as we have seen relies on the additionality of avoiding deforestation in favour of conservation. Up steps FSC which says that in this case, “FSC Certification should be a prerequisite for a carbon finance initiative”.

Suddenly you have a forestry certificate when you should have an ‘avoided forestry’ or conservation certificate.

I think that the reason for this is that we lack the ability to verify the benefits of conservation.

The closest tool we have which can audit additionality, permanence and leakage in a forestry scenario is a system like FSC. It’s like trying to prune your roses with a chainsaw

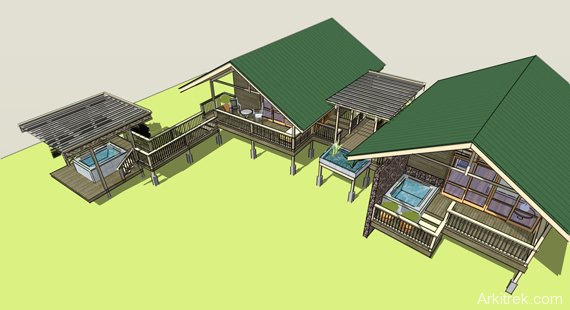

Mike Packer is working on a complete ecosystem service certificate which offers hope of a more suitable tool which is not dependent on additionality. The pilot projects under discussion mostly involve rehabilitation of degraded or fragmented forest but I understand that once proven they could be applied to intact forests.

The ArborCarb certificate relies on science that identifies, evaluates and sells (to suitable customers) all of the services provided by an ecosystem. Significantly these certificates are not for sale as an offset product, which will help tackle the leakage problem. i.e. when land protected/rehabilitated in one area indirectly or directly causes degradation in another. The holistic approach also means that ecosystem services are less susceptible to double selling.

By removing the need to demonstrate additionality, the ArborCarb approach may be able to provide the ‘other means’ of rewarding countries with low rates of deforestation that I mentioned above.

Until we can achieve this I fear that it will be difficult to resist temptation; such as in Indonesia which this week reneged on a moratorium against planting oil palm on former peat swamp forest. Commentators see this as either a ploy to benefit industry ahead of elections or perhaps a ruse to increase potential earnings under future REDD projects. Or perhaps both?

The positive bit

Meanwhile most of the conservationists that I know support PES projects such as the Malua Biobank. They have chosen to be lenient on the history and controversy of Malua because the project represents an innovative experiment that may lead to a new model for engagement between industry and conservation.

‘At the very least even if the project only succeeds in putting a ring fence around 30,000ha of forest and prevents it’s conversion to plantation, then it will have been a success’ comments a friend of mine.

Sabah was at the vanguard of carbon finance 15years ago with the Infapro Project. Now it is pioneering biodiversity conservation certificates and could soon be leading the way in implementation of ecosystem services certificates which are not burdened with the tyranny of additionality.

More on ArborCarb at the Oxford Centre for Tropical Forests

More on Malua Biobank from Katoomba

More on Malua Biobank from Mongabay

Related posts

%RELATEDPOSTS%