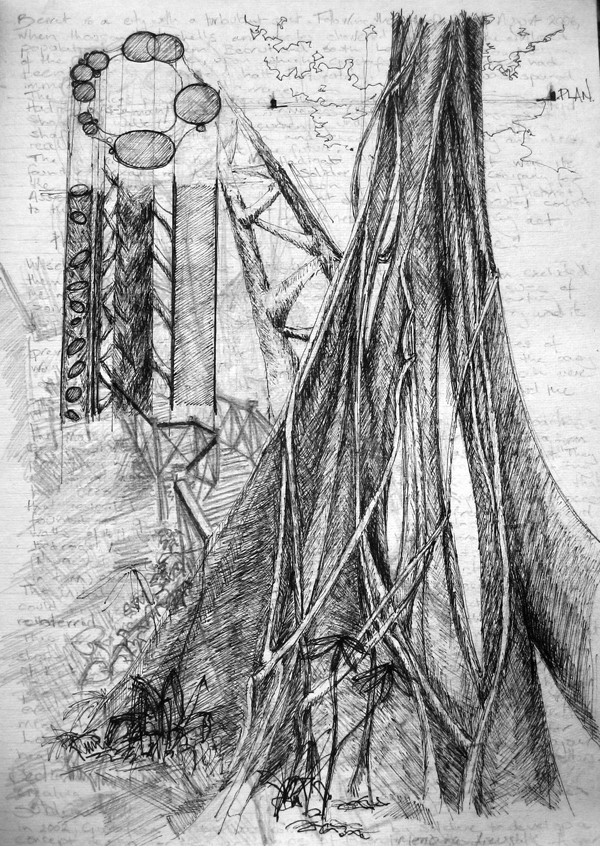

The Tower to The Memory of a Tree

Text and images by Sarah Greenlees

Starting as an epiphyte and often ending up as freestanding trees, strangler figs (genus ficus, subgenus urostigma) are dynamic and dramatic members of the forest structure, they can also be surprisingly architectural.

Degrees of Enclosure

Though all the forest provides shelter in some capacity, figs provide it in a very literal, enclosing fashion, at a series of scales. On the smallest scale, protective shells lined with spongy material and flowers provide shelter for tiny gall wasps. These fig syconia later develop into fruit. Here the female wasp will die after laying her larvae, but they also provide a safe place for larvae to develop, for wasp mating to take place and finally, for safe passage into the surrounding environment. They are a place of rest and a place of rebirth. At the large scale, the fig is an organic tower block providing shelter for pythons, frogs, geckos and birds. Almost in the manner of Ian Banks’ ‘The Bridge’ all sorts of animals live between the structure at different levels.

Compound Structures

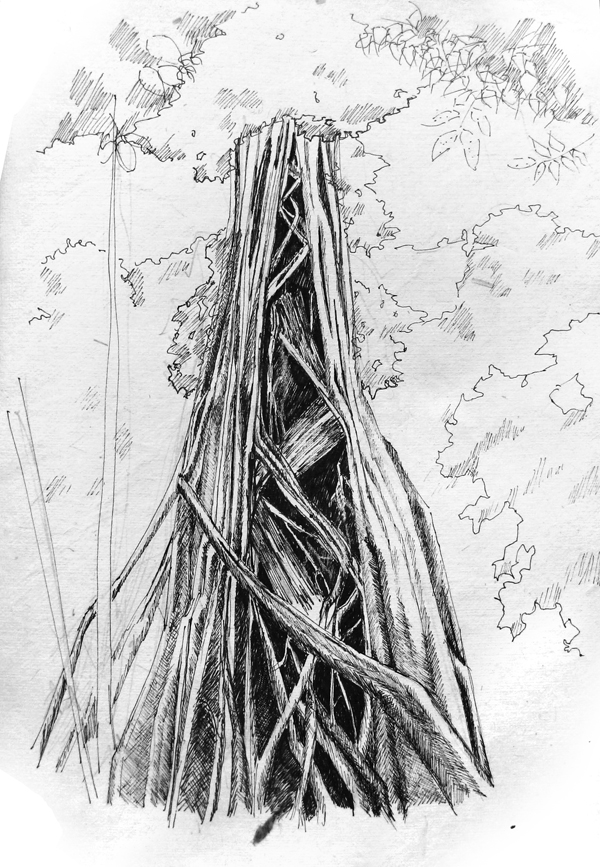

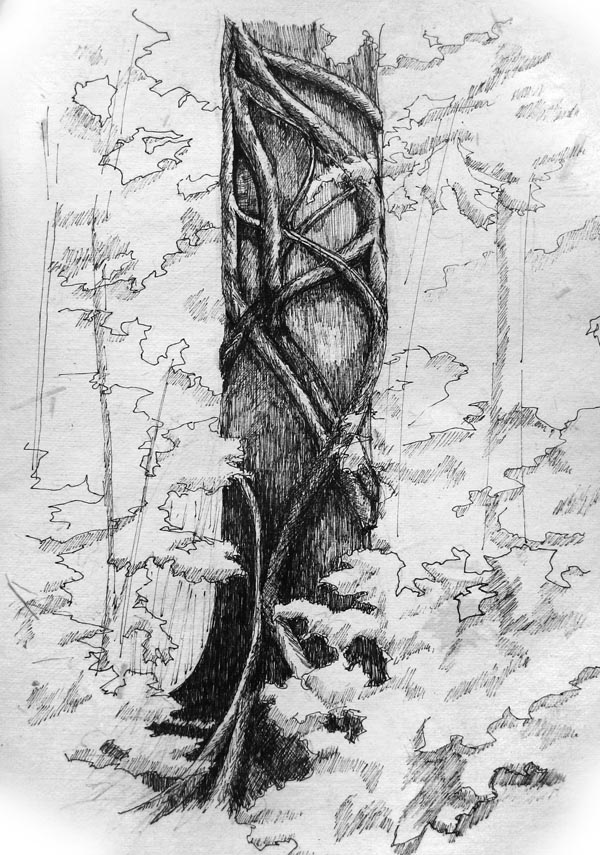

This structure of the strangler figs is clearly legible – in architectural jargon it could be called celebrated. It occurs out of a sequence of growth. In common seed dispersal tradition, animals deposit seeds in their droppings in the branches of other trees. Making rapid development as an epiphyte, the fig grows and sends down aerial roots to the forest floor becoming a hemi-epiphyte (1).

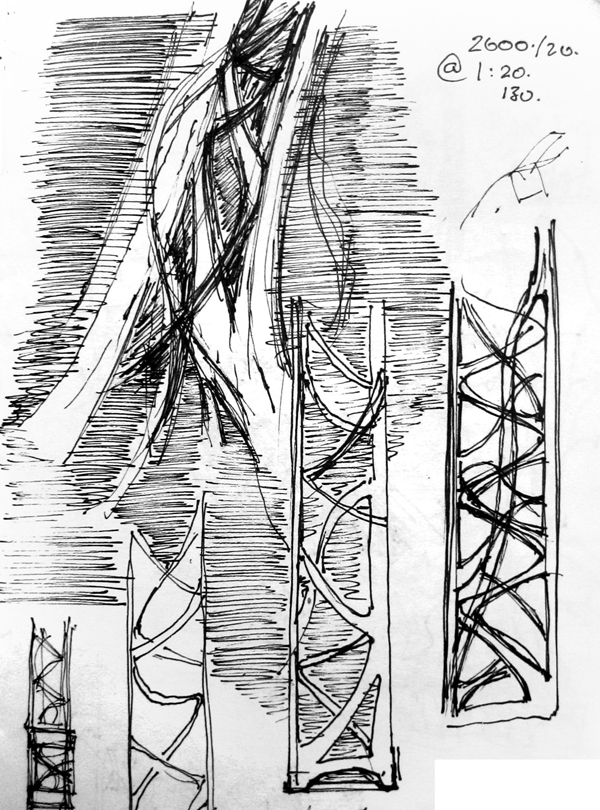

Winding around the host tree and ascending back up to the heights of the canopy – a hemi-epiphyte becomes a parasite (2). The vines are strong, resilient and unassailable and their resultant patterns are a composition of elements in compression and tension. Primary roots of thick circular section become flying buttress when in filled with slender walls at the base. As these buttresses meet the centralized structure, thinner lines traverse the intermediary spaces, stretched between the primary elements in tension. Triangulated compound beams of soft wood are created that are always developing; continually being added to. In a dynamic and dramatic display over time the host tree is finally broken in several places, crushed, twisted and sometimes left hanging in a cathedral like arrangement of root columns.

Complex Symbiotics

The fig tree and the gall wasp survive by means of a unique symbiotic relationship. In return for the protective, flower lined shell; the female gall wasps are the sole pollinator for the figs. The relationship relies on a range of flowers of different lengths to match the anatomy of the wasp. As the wasp larvae develop within 3 – 20 days and the adults only live for a couple of days, so the symbiosis also relies on either the fig tree having syconia at different stages of development, or on there being a high population of figs of the same species in a given area. In an astounding display of biodiversity there are, in most cases, specific species of wasps for specific species of figs. This prevents cross-pollination and allows numerous fig species to grow together, sometimes up to 70 species in close proximity. The advantages of such ‘species packing’ in a forest where many of the animals may at some time be dependent on figs are clear. The system is a careful balance of chemical precision and statistical probability.

Of course, a similar relationship exists between man and his environment. Being surrounded by such a sensitive landscape as the Danum rainforest makes this all the more apparent. The revenue that Borneo Rainforest Lodge generates makes it imperative to the survival of the forest, and the forest is the reason for the lodge’s existence. How such a relationship develops is of keen interest. As the rainforest continues to create business for the lodge, how will the lodge further the conservation of the forest? Already their efforts to overhaul the typical practices of the hospitality industry, to green practices are admirable. And their continued search for new ways to promote conservation are very positive. But there is a long way to go and it requires passionate management.

Echoing the Past

At different instances in the design at BRL references are made to the organic weave of the fig vine within a clear and ordered structure. However, the visibly progressive structure of the fig tree is a reminder that the environment is a live, ever-changing one. Our buildings will fit in to the landscape and grow with it. Traces they leave behind have the potential to highlight the ever-changing landscape. Already there are signs of man’s intervention with nature – the boardwalk bends around the trees and when these fall their memory is marked by the path of the structure. A palimpsest of growth develops.

At different instances in the design at BRL references are made to the organic weave of the fig vine within a clear and ordered structure. However, the visibly progressive structure of the fig tree is a reminder that the environment is a live, ever-changing one. Our buildings will fit in to the landscape and grow with it. Traces they leave behind have the potential to highlight the ever-changing landscape. Already there are signs of man’s intervention with nature – the boardwalk bends around the trees and when these fall their memory is marked by the path of the structure. A palimpsest of growth develops.

This reflects possibly the most poetic element of the fig tree development Once the fig is truly established as a freestanding tree and when the host tree has entirely disappeared the fig tree becomes a hollow tower with foot holes to climb.

It is an almost accessible starting point for a journey through the canopy. An ascent to the sky seems possible, if it weren’t for the fear of cobras, it is as tangible as the taste of wet soil in the air. The view from the top through the leaves and out across the canopy must be incredible. You can imagine the climb up being frequented by glimpses through the structure and then as you reach the top – the first clear view, like looking out over a parapet of a tower, straining to see before you’ve quite reached. And then to sit and look out. To be in a small, enclosed, protected space with an immense vista before you. Bacchelard’s attic pales into insignificance.

At the end of the fig tree’s story is a strong, tall structure of an ex epiphyte. But what is also left standing is the imprint of a tree, a hollow space that echoes of the past. A dark resting place of forest spirits, a hot and humid miasma, a shelter for geckos and bats, bees and pythons; a glimpse of the sky reaching high through a top heavy mass of tiny delicate pin prick leaves. It is the negative space of a trace of the past- the tree that was. Here is the tower to the memory of a tree.

Footnotes

(1) In a paper published by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization of Australia, Schmidt and Tracey hypothesized that this change in behavior is brought about by a change in nutrient levels.

(2)Though called strangler figs, it is often not the cause of death to the tree. Rather, it is often the rapid grown of leaves and roots as the host loses the competition for light and nutrients. In the process of strangulation, the xylem and phloem layers around the outside of the host trunk are closed off in the ever-increasing pressure of the fig growth.

References:

SCHMIDT Susanne ; TRACEY Dieter P. ; Adaptations of strangler figs to life in the rainforest canopy; Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, Collingwood, AUSTRALIE (2002) (Revue)

Website References:

Figweb; Iziko Museums of Cape Town accessed on 23 Jan 10

The Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation assessed on 23 Jan 10

Stranglers and Banyans accessed on 23 Jan 10

zipcodezoo accessed on 23 Jan 10

Mongabay

Related posts

Great article, i have always been fascinated by strangler figs and as an artist they feature prominently in my artwork, the borneo rainforest lodge must have a number of figs growing around it then? i certainly hope this symiotic relationship between man and forest becomes stronger and stronger, hopefully leading to other countries investing in standing forest rather than clear felling it all for short term profits which is so often the case. in this day and age of global warming and environmental destruction rainforest expansion should be a major industry. their worth is priceless both for the rainfall they generate the carbon they can soak up but also for their stunning beauty.